Keeping the Connection Alive

Former UNM Dean Chronicles His Journey Back to Walking after Injury

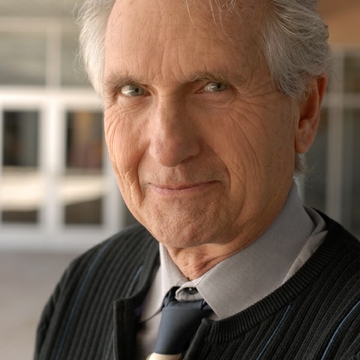

Jim Linnell was just months away from retiring as dean of the University Of New Mexico College Of Fine Arts in 2012 when he and his wife Jennifer stepped off a porch for a post- dinner walk by the beach during a Mexican vacation. The two mistakenly thought there were steps at the end of the porch. Both fell a few feet. She dusted herself off. He was paralyzed for more than a year.

Today - thanks, he will tell you, to his family, a long list of various therapies along with surgery at UNM Hospital - he has had a near- miraculous recovery and moves confidently with a walker.

Some 17,500 people in the U.S. will sustain a spinal cord injury every year. They are known as "incomplete" if, as in Linnell's case, the spinal cord is not completely severed. The injuries are both frightening and confounding and there are few ways of predicting at the outset how much physical function can be restored.

Linnell, now 78, recently detailed his recovery in his memoir, Take It Lying Down, Finding My Feet After a Spinal Cord Injury published by Paul Dry Press available on Amazon. Along with his wife and family, he credits his recovery to being able to draw on a lifetime of teaching in the arts and a love of great literature that provided examples of suffering and enduring.

"There are two things that happen in a rehab like this," he says. "There is the physical, medical story of your body and then there is mental, spiritual story as you come to terms with the death of who you were and how much effort you are able to invest in being this new person defined by the compromise to your body."

In writing of the experience, Linnell says he wanted to first "show who was the man who stepped off that porch" and then trace together how the mental and spiritual elements of his healing slowly melded to make him the man he is today.

"No medical facility or PT can teach you that - they only can warn that if you succumb to isolation and depression then it is an inevitable, downward slope and you will never get better," he says. "You will withdraw - from the world, from contact, from effort - and eventually you will be in deep trouble."

The story begins with being airlifted directly to UNM Hospital from Mexico the day after the fall.

"I knew the accident was bad because I could not move, but I didn't want to believe it was that bad," he says.

He credits Andrew Patterson, MD, associate professor in UNM's Department of Orthopedics & Rehabilitation, with keeping him from being permanently paralyzed.

"I had an injury at C4 - a bone just poked the spinal cord. If it had continued to swell unstabilized, then I am sure I would have had more trouble in being rehabbed to a walker," Linnell says.

Linnell doesn't recall the length of his surgery or the total number of days he spent in the ICU, but he does remember the seemingly endless pilgrimage of well-wishers - none of whom he could speak with since doctors had inserted a tracheotomy.

"A lot of people knew me. I was dean of the College of Fine Arts and had just run for provost, * so there was a steady stream of visitors - none of whom could understand a word I was trying to say!"

But it was an early sign of a drive to stay connected to the world that he and his family would later build upon.

Because spinal cord injuries are so complicated, most experts recommend that patients undergo rehabilitation at a specialized hospital. Patterson recommended Craig Hospital in Denver. Known as the place where "Superman" actor Christopher Reeves underwent rehab after his paralyzing fall from a horse, it specializes in patients with spinal cord and brain injuries.

"Craig was just the right place to send me," Linnell says. "They take quadriplegics and teach them how to be quadriplegics - which is not a simple thing to be."

The staff at Craig was unrelentingly positive, yet had few short- or long-term goals for him.

"All they tell you is, 'This is what has happened to you and we are going to do the best we can to do rehab and we will get whatever we will get. But we are going to teach you how to live with wherever you are,'" he says. "For me, that meant I was still a quadriplegic."

But they did open one window of hope. As an incomplete spinal cord injury patient, they said he might see some improvement within the first two years.

"During my time in Craig, I am emotionally all over the map," Linnell remembers. "Mostly I am in denial, thinking this cannot last, this is not going to last. However, you cannot think too much about it because your body is such a wreck."

The Linnells arrived at Craig in January and by April, "I am being released home as a quadriplegic with glimmers of opportunity in my legs," he says. "I have had some sensation and movement there. My right arm can do some things. My left arm is useless at the time."

"We go home and for another one and a half years, I am still a quadriplegic."

At first, the post-rehab terrain seems terrifying.

"At Craig, I was in physical therapy two hours and then I was in one type of rehab situation after another," he says. "When I was not working with a PT or an OT, I was in an education class. I came back to Albuquerque and said, 'Oh my God, how will I replace all that?'"

Their Albuquerque home sits on two acres, and now he could no longer take part in the upkeep. "My wife is both general and solider," he says. "Yet the logistics needed to just get me up, dressed and fed are overwhelming."

Yet early on, he discovered his insurance only allowed 10 physical therapy visits yearly.

"It makes no sense," he says. "They say, 'We know you are a spinal cord patient and will need PT for the rest of your life,' yet you are given this limited amount of therapy annually." Linnell also laments that physical therapists are hobbled by having to prove strategies to insurance companies and that today's medical system is not set up to deal with a chronic injury that can be helped but not fixed.

"Therapists should be allowed more freedom," he says. "Every patient is different. With my situation, it is going to be a narrow range of improvement, and it is going to have to be sustained."

The cavalry appeared when his sons arrived for a Fourth of July visit with plans of installing an overhead walking track running the length of the porch replicating the one he had been using at Craig.

"So every morning I would get up and get dressed then walk back and forth on the track and then have PT," he says.

Jennifer, also a retired UNM professor, had introduced Pilates to the UNM dance program and taught a popular beginning mat class that had a healthy following among football players. So it was decided that Pilates would replace PT. Some research also found a local acupuncturist, Dr. Jason Hao, who is involved with groundbreaking cranial acupuncture work. Visits to him were added into the daily rotation, in addition to endless rounds of visits with doctors, urologists and physiatrists.

"I have always been an optimistic person, and often been accused of being a Pollyanna," Linnell says. "My immediate inclination is to think, 'Well, how many things can I do to overcome this?'

"Yet it is hard to even imagine it is going to get better, and all the work you do hurts. It is not as if you go to the gym and get the stiffness out of your body, get warmed up and go until you love it. You never love it! But, you think, 'If I keep working at it, maybe I will get better.'"

Then the rounds of doctor and exercise visits began to pay off, with progress seeming to come almost all at once. Linnell regained bodily functions. Being able to stand grew into being able to take steps without the walking track. A walker replaced the wheelchair, and fingers, hands and arms began to do his bidding. Being approved to drive a car gave him independence and mobility.

"Once we were doing well, we became so excited," he says. "We thought, 'Let's go, let's go, let's go!"

On a return visit to the Denver rehab hospital, "I am the kid who thinks I just won the pony at the fair and I expect everyone to cheer - and they did - but no one was curious as to what we did since leaving that would bring me back in a walker instead of a wheel chair," he says. "They just dismissed it once they heard it was within the two-year window for change."

Linnell and family continued the multiple therapies for some time, but then progress did slow.

"I realized after a while that we had crossed the finish line we had been given and it was time to make a choice - am I going to dedicate my life to being in rehab rooms all my waking hours or am I * going have a life, do the things I love and not become this obsessed creature with a goal that is always out of reach."

He still holds to an exercise schedule and does some PT, but not with the intensity of the first few years.

"My wife is a constant task manager," he says with a laugh. "She says, 'Get up! You are not walking enough! You are not moving enough! Get away from your computer! Thank God for her!" In many ways, Linnell is a new man. Having completed his memoir surrounding the accident, he is now * writing a new novel. He speaks of his experience to the first year class in the medical school. He drives, keeps up with friends.

"I think I know my body now, and it is still not fun. It tortures me with spasms. There are good days and bad days. But, it is also a body that allows me to do so many things. I have bodily function. I can drive, I can dress myself. These are huge gifts I have been given."

"That need to connect is the force that saved me," he says.

"How much do you want to be in the world, to be out doing things and seeing people, to be defined - not by what you can't do - but to work with what you can?"