Keeping the “ER” out of SummER Fireworks Fun

Nursing Practice in a Novel Pandemic

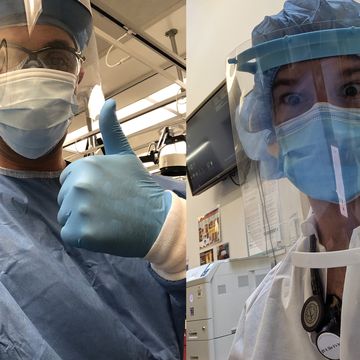

UNM College of Nursing Graduate Students Care for COVID-19 Patients on New York’s Front Lines

Journal Entry, Monday, April 6: "I met around 60 people today, but I know no faces. Every staff member is wearing a suit of PPE. I've worked on two continents, in seven hospitals, and never seen anything like this. Six to 12 critical vented patients to each nurse. One N95 mask for five shifts. Vitals machines out of battery, extension cords running every which way. No one complained. No one gave up."

Alex Perrin was halfway through his Master of Science in Nursing family nurse practitioner studies at The University of New Mexico College of Nursing when COVID-19 changed everything. A former travel nurse with emergency department expertise, he knew his skills would help New York City as infections surged.

Within days he was in a Brooklyn hospital, dealing with a reality few outside those walls truly comprehend, that his journal helps him process.

At the same time, Kris Jackson, a UNM College of Nursing PhD student and critical care nurse practitioner, joined an overburdened ICU team in the Bronx.

"I anticipated an ICU full of people with comorbidities or advanced age and that wasn't the case," he said. "I treated a substantial number of people in their 30s and 40s who succumbed, not just people who were obese, diabetic or had underlying lung conditions. I wasn't ready for that."

Jackson spent two intense weeks in New York before returning home. He lives and works in San Francisco, and chose UNM for his doctoral work because its well-established hybrid program enabled him to continue his clinical practice. He was given leave to volunteer because his city was successfully managing its COVID-19 caseload.

Perrin is still working in Brooklyn and expects to be there through the summer. With classes moved online, this adventurous full-time student realized he could do his online work from anywhere, and his professors encouraged his intention.

"Alex and Kris exemplify what it means to be a nursing student at the University of New Mexico," said College of Nursing Dean Christine Kasper, "going above and beyond, and driven by their calling to serve our nation where it was most needed at the time."

Although their New York hospitals served uniquely diverse neighborhoods, their experiences, realizations and concerns have a lot in common.

The demands of COVID-19 care put staff in constant crisis mode. Patients cannot see their caregiver's faces, and those caregivers can't linger at a bedside.

"The Red Zone here is the critical care bay of the ED, built for a maximum of 15 patients," Perrin noted. "The first week I was here, there were 30 to 35 in that zone at all times. Each nurse was taking care of six to 12 patients, every one was on a ventilator, most were dying. You run in and put out whatever fires you can, then run to the next room. Patients are reaching out, they're scared, and you really want to help them, but you have more waiting."

Pharmacies scrambled - and sometimes failed - to keep up with orders for every conceivable medication, and supplies and equipment were not always available as needed.

"I've never been in a situation where we're having to make clinical decisions based on supplies," Jackson said. "We were converting space all over the hospital into ICU beds. There was no shortage of ventilators, but there was a shortage of access to dialysis, nasal cannulas and negative pressure rooms to avoid spreading virus particles. Every time I'd run a checklist I'd realize, 'I don't have this piece of the puzzle.' You'd have to pivot and find a creative solution."

As New York's situation grew dire through March and April, thousands of medical professionals from across the nation raced to assist. Although the need for additional hands was immense, the necessary skillsets weren't always met.

"Some nurses worked in clinics or nursing homes, and some had inpatient experience, but not in an ICU," Jackson noted. "The attending physician that day might be from primary care, or a surgeon. I was comfortable with vent management and navigating airway problems. It's a good time for NPs working in critical care to shine; it really shows our value as integrated parts of the ICU team. We were well received, and our advocacy and input were respected. We were seen as the leaders of the team."

There were constant battles, too often lost, to save the lives of critically ill patients.

"Four patients died in the first half of my first day, and the number kept going up from there," Perrin wrote. "I might meet a patient when I came in to work, and they are talking to me. By mid-shift they may have declined so rapidly we had to intubate them. I've seen so many body bags, and never met those families. The morgue was so full they had to bring in two refrigerated trucks."

Unable to be with their loved ones, anxious families depended on hospital staff for information. Thousands of compassionate calls were made.

"The few occasional minutes we were able to spend on the phone with families was the only time they had any clue about what was going on," Jackson said. "They had no idea when patients were being moved between units, or institutions. These calls were at the top of our list, a matter of supportive care, keeping them updated as candidly and accurately as possible. At least they got a consistent message leading up to the day they might get the call saying their loved one had passed."

For Perrin and Jackson, the exponential fatigue of 12-hour shifts with scant down time was balanced with camaraderie, generous donations of food from the surrounding community, and deep appreciation for their New York colleagues.

"The staff who live here have been the backbone of the response," Perrin said. "The horrifying conditions I experienced the first week they endured for well over a month. Most nurses are living in hotels to isolate from their families, and they may have permanent scars on their faces from wearing masks every day."

"I had the luxury of being a transient volunteer who worked very hard for two weeks," Jackson stated. "The dedicated nurses doing this 24/7 for weeks, at the expense of their own health - they are the rock stars. They show up and do the work every day. That is a true definition of hero."