A few years back, Douglas Ziedonis collaborated with a percussionist friend to record The Journey, a collection of hauntingly atmospheric pieces performed on traditional Native American, Latvian and African wind and string instruments.

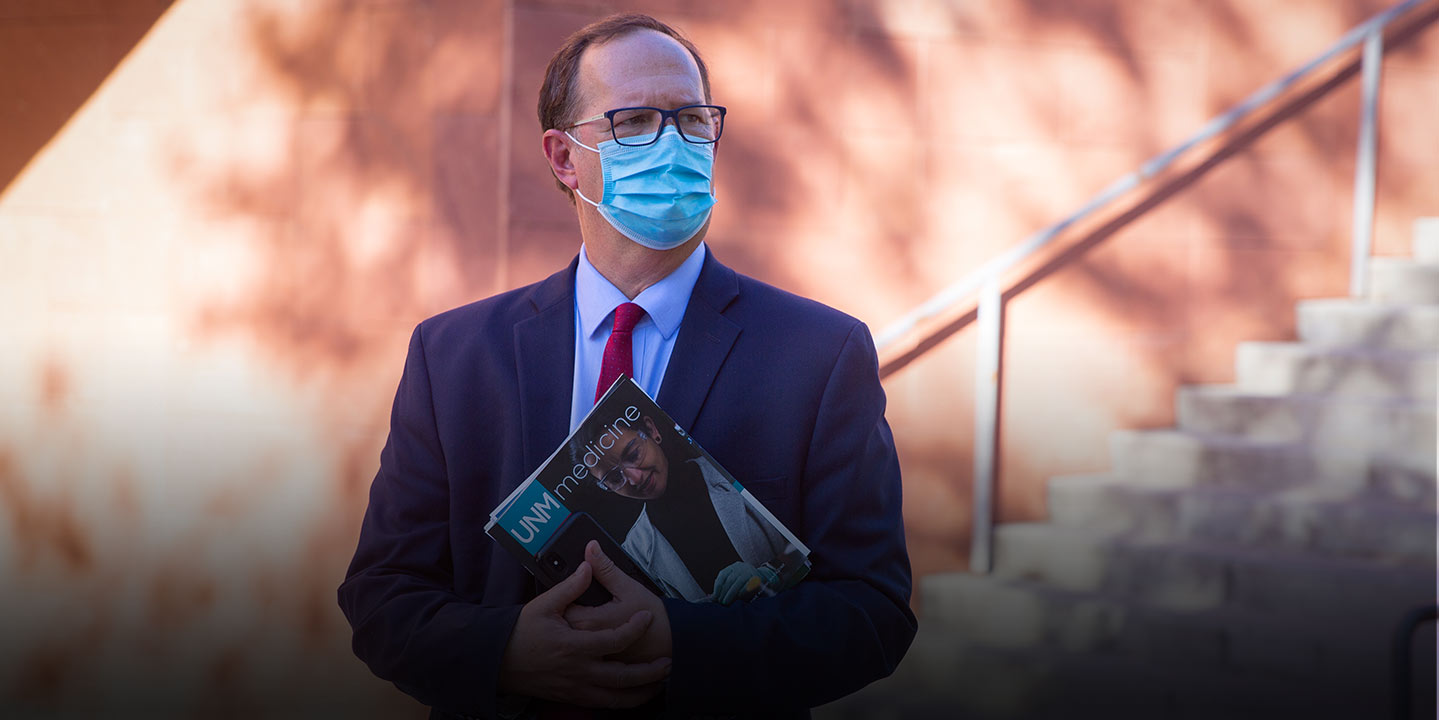

The album’s title aptly describes the career path of a son of Latvian immigrants who would go on to become a prominent addictions psychiatrist, researcher and administrator – and now Executive Vice President for Health Sciences at The University of New Mexico and CEO of the UNM Health System.

Ziedonis, who assumed his new roles on December 1, brings eclectic interests and decades of experience in academic medicine. He has lost no time in getting to know his new colleagues and mastering the minutiae that come with the job.

“I feel like I’ve been here months, rather than days,” he says in an interview just before the winter holidays. He has been appraising Health Sciences colleges and programs, looking for opportunities to expand or forge new partnerships.

“There’s a really great group of leaders that I get to work with in Health Sciences and on Main Campus,” he says. “It has been in the middle of the acceleration of the pandemic, which has been the most challenging moment in my career. I feel strong pride for our terrific workforce here, who are on the front lines.”

Ziedonis, who most recently served as Associate Vice Chancellor for Health Sciences at the University of California, San Diego, has also been on faculty at Yale, Rutgers and the University of Massachusetts. He and his wife, Patrice, have crisscrossed the country since meeting while he was doing his psychiatric residency in California.

Now, they’re happily renting a house in the High Desert development in the Sandia Mountain foothills and enjoying New Mexico’s unique climate. “We love the idea that it can snow in the morning and with the sun it goes away,” he says.

Early Years

Ziedonis grew up in Bethlehem, Pa., where his father, who emigrated from his native Latvia following World War II, was a Lutheran minister and a college professor.

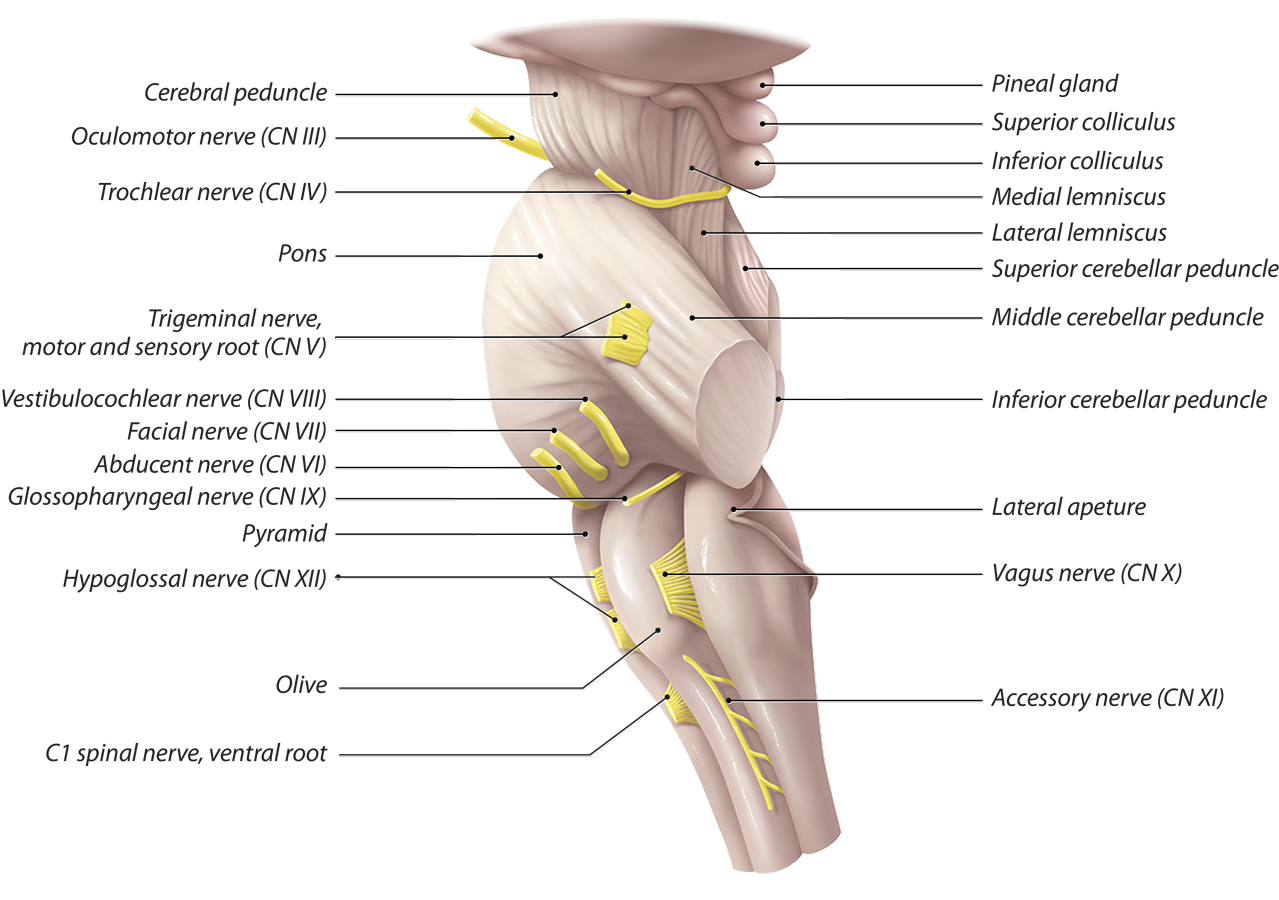

After graduating Davidson College in North Carolina, Ziedonis attended medical school at Penn State with the thought of becoming a family doctor, but he changed course after a friend urged him to apply for a grant from the National Institutes of Health for a study measuring cerebral blood flow in sheep. Ziedonis was bitten by the research bug and found a growing interest in the functioning of the brain.

In 1985 he moved to UCLA for a residency in general psychiatry, joining colleagues who were conducting cutting edge research in cocaine addiction using positron emission tomography (PET) to image changes in the brain. In the lab next door, another team was using PET scans to study talk treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder. “This was a game-changer for me, because it was the first study showing that the brain changes with psychotherapy,” he says.

Ziedonis completed an addiction psychiatry fellowship at UCLA, then moved to Yale in 1990 as an assistant professor, where he had his hands full.

“I was the medical director for a methadone clinic that had 750 patients,” he says. “Forty-five percent of them were HIV-positive, and we had no solution for them at that time. I had a hundred patients that were pregnant. God brings you things you’re not expecting.”

Meanwhile, he was also developing a program to treat people with co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse diagnoses. “I had 350 additional patients that were in an outpatient medication-free clinic,” he says. “I also ran an evening intensive outpatient program with patients. I did consults, and I had my own little outpatient clinic. So I was extremely busy clinically.”

Ziedonis managed to find time along the way to complete his master’s in public health. “That was the game-changer for me in becoming a serious physician-scientist with the ability to have independent funding,” he says.

In 1998 he moved to Rutgers University, where he expanded his interests to encompass treating tobacco addiction, working with Dr. John Slade, an acclaimed researcher and tobacco industry nemesis.

Spirituality Shapes Research

Ziedonis has nurtured a lifelong interest in mindfulness and spirituality that has helped shape his priorities as a researcher, clinician and administrator. “I was taught to pray early in life, and I remember very young, that was something that was important,” he says.

In college, he studied Chinese philosophy and Buddhism and practiced Transcendental Meditation. A few years later he became acquainted with the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn, a molecular biologist at the University of Massachusetts who melded elements of Zen meditation and yoga into a secular therapeutic modality known as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR).

“When I was at UCLA in the 80s, I started to integrate some mindfulness into my clinical practice,” Ziedonis says. While at Rutgers, he also served as a visiting professor at the Princeton Theological Seminary. “For me, spirituality also aligns with diversity, because we’re of different faiths,” he says. “Understanding someone’s background and what matters to them – what are some of their core beliefs and values – that’s an important window, even if you aren’t coming at it from a faith-based point of view.”

Ziedonis joined the UMass faculty as tenured professor in 2007 and got to work firsthand with Kabat-Zinn and his Stress Reduction Clinic. “They weren’t used to a psychiatrist being open to that,” he says. “In my department we integrated it into all our teaching, research and clinical work. Then I got really well-grounded in MBSR and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.”

While at UMass he also ran a mindful physician leadership program, and when he moved on to UCSD in 2017 he brought the mindfulness-based leadership training with him. “It’s now a course in the medical school for the students,” he says.

Ziedonis also agreed to serve as executive director of UCSD’s Center for Mindfulness, in addition to his other duties. When the pandemic forced the shutdown of campuses across the country, he helped create an online resource where people could come together to meditate virtually three to five times a day, as well as a collection of recordings they could access any time. “We’d get about 200-plus people a day, and we would get over a thousand people a day with the recordings,” he says.

“The blending of mindfulness and self-compassion work are really some important skills for clinicians,” he adds. “Doctors are really tough on themselves. They expect themselves to be perfect, and they have a really high bar. So, learning ways to just be OK with yourself – the shared common humanity, having some kindness to yourself.”

Closeted Musicologist

When it comes to his serious hobby of collecting and playing traditional musical instruments, Ziedonis calls himself “a closeted musicologist.” He performs on a Latvian woodwind instrument called a stabule and the kokle, a stringed zither. He has played African instruments, including the djembe, balafon and kora, and he has an extensive collection of Native American flutes made by Navajo and Jemez Pueblo craftsmen, among others.

“I like to learn about music and culture of different groups,” he says. “Throughout my career, I’ve taken a Native American flute on my travels.” On a research trip to Crete, he and his wife decided to visit a music shop to sample traditional Greek instruments. “Suddenly, we’re in some back alley, and nobody knows English, and I don’t know Greek – and she’s like, ‘How did we get here?’”

Ziedonis pulled out his flute and started jamming with the local musicians. “For me, those are some fun things about traveling,” he says. “I think of music as a language of communication. When you don’t have the other language, you can have that.”

The couple’s son, Mason, lives in New York City, where he works for Goldman Sachs. Their daughter Michelle, who has a master’s degree in dietetics, spent part of 2020 working at a Los Angeles VA medical center that was filled with COVID patients. “We can appreciate the front lines and all the pressures on families where they have to deal with that,” Ziedonis says.

Still, he knows the pandemic won’t last forever. “The spiritual side, the meditative side of me just loves being in New Mexico and is looking forward to the non-COVID times and more travel,” he says. “I’m really attracted by all the diversity that’s here – the history and the cultures.”

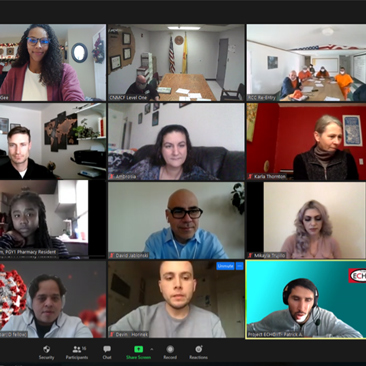

“Like many across the UNM Health System, our team is adapting our service model. Not only are we meeting the needs of our patients but also the needs of patients across the country,” says Fabian Armijo, director of Interpreter Language Services and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at UNMH.

“Like many across the UNM Health System, our team is adapting our service model. Not only are we meeting the needs of our patients but also the needs of patients across the country,” says Fabian Armijo, director of Interpreter Language Services and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at UNMH.

Construction is underway on The University of New Mexico Center of Excellence for Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation, a new facility on the UNM Health Sciences Rio Rancho Campus that will unite clinical, educational and research activities under one roof.

Construction is underway on The University of New Mexico Center of Excellence for Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation, a new facility on the UNM Health Sciences Rio Rancho Campus that will unite clinical, educational and research activities under one roof. Salas, who currently operates three laboratories at the UNM Health Sciences Center and the UNM School of Engineering, typically has five to 10 graduate students and between 10 and 15 undergraduates working at any given time.

Salas, who currently operates three laboratories at the UNM Health Sciences Center and the UNM School of Engineering, typically has five to 10 graduate students and between 10 and 15 undergraduates working at any given time.

Sarah Adams, MD, a gynecologic oncologist and cancer scientist, hopes her national clinical trial may not only help women fight ovarian cancer but also keep it contained.

Sarah Adams, MD, a gynecologic oncologist and cancer scientist, hopes her national clinical trial may not only help women fight ovarian cancer but also keep it contained.

The idea is to create “courageous conversations” among students, faculty and staff, Wallerstein says, adding that discussions have also focused on policies and practices regarding hiring and retention policies for faculty of color and the university’s policies in terms of salary equity. “We’re trying to transform our entire unit, because we’re small and have the capacity to implement a lot of changes faster.”

The idea is to create “courageous conversations” among students, faculty and staff, Wallerstein says, adding that discussions have also focused on policies and practices regarding hiring and retention policies for faculty of color and the university’s policies in terms of salary equity. “We’re trying to transform our entire unit, because we’re small and have the capacity to implement a lot of changes faster.”

Patricia Watts Kelley, PhD, APRN, the new associate dean for research and scholarship in The University of New Mexico College of Nursing, has a vision for students and faculty based on her view that a successful career involves continual professional growth and mentorship.

Patricia Watts Kelley, PhD, APRN, the new associate dean for research and scholarship in The University of New Mexico College of Nursing, has a vision for students and faculty based on her view that a successful career involves continual professional growth and mentorship. “My goal is to have UNM nursing faculty ready to address the (state’s) health care needs for the next 20 to 50 years, whether it’s during a pandemic or addressing complex chronic conditions by giving patients the tools to manage their own care with some guidance,” Watts Kelley says.

“My goal is to have UNM nursing faculty ready to address the (state’s) health care needs for the next 20 to 50 years, whether it’s during a pandemic or addressing complex chronic conditions by giving patients the tools to manage their own care with some guidance,” Watts Kelley says.

Dayao first focused on creating processes to regulate the number and flow of patients physically seen at the UNM Cancer Center. During the first months of the global pandemic, the Cancer Center remained open and continued to provide care for patients on active treatment, but it transitioned nearly 30% of its patients to telephone visits.

Dayao first focused on creating processes to regulate the number and flow of patients physically seen at the UNM Cancer Center. During the first months of the global pandemic, the Cancer Center remained open and continued to provide care for patients on active treatment, but it transitioned nearly 30% of its patients to telephone visits. Originally from the Philippines, Dayao received her medical degree in Integrated Liberal Arts and Medicine Program at the University of the Philippines – College of Medicine.

Originally from the Philippines, Dayao received her medical degree in Integrated Liberal Arts and Medicine Program at the University of the Philippines – College of Medicine.