New Hope

Researchers Study Fresh Approach for Treating Severely Depressed Patients With Electroconvulsive Therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) provides relief to many severely depressed people, but the procedure, which delivers pulsed electric current to induce seizures in the brain, entails a delicate balancing act.

Patients whose brains receive too little current don’t see enough antidepressant benefit. Too much, on the other hand, can cause short-term memory loss and other cognitive side effects.

“Everybody that currently receives ECT receives the same current,” explains Christopher Abbott, MD, associate professor in The University of New Mexico Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences and medical director of the Electroconvulsive Therapy Service. But no two people are alike: brain volume, skull thickness and other factors affect how much current gets to where it needs to go.

“Everybody that currently receives ECT receives the same current,” explains Christopher Abbott, MD, associate professor in The University of New Mexico Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences and medical director of the Electroconvulsive Therapy Service. But no two people are alike: brain volume, skull thickness and other factors affect how much current gets to where it needs to go.

Now, thanks to a five-year $3.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, Abbott and associate professor Davin Quinn, MD, are testing a new approach to ECT that could more closely tailor the treatment to each individual’s needs.

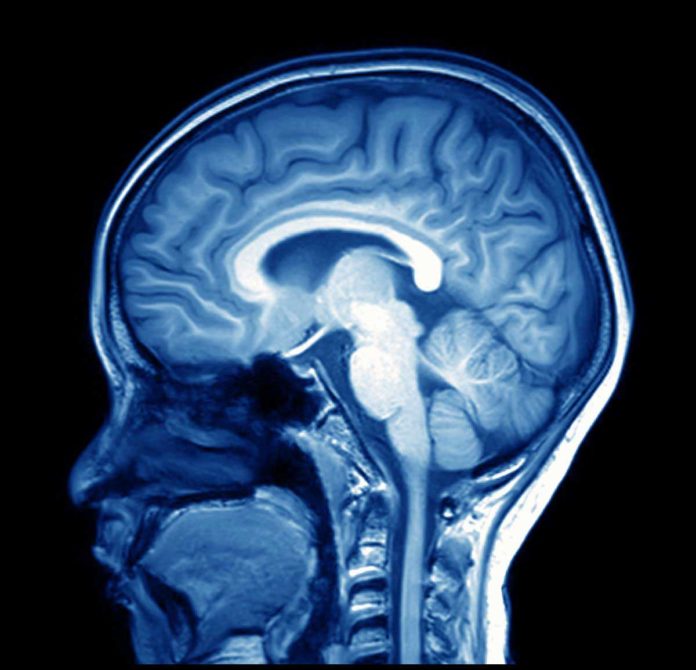

Drawing on earlier studies involving animal subjects, the team will gradually dial up the amplitude of the electrical current to the point of inducing a seizure. Then, with the help of magnetic resonance imaging, they’ll calculate how far above that level they need to go to achieve a therapeutic response.

They hope to provide precision dosing relative to traditional ECT, sparing patients from cognitive problems. And if the method works, it could easily be adopted by other clinicians.

The brains of depressed patients show signs of atrophy, Abbott says. ECT is known to increase the volume of the hippocampus, a brain structure closely associated with depression symptoms, and researchers suspect that the electrical field stimulates neurons to grow stronger connections with one another, reversing the depression.

“We refer to it as neuroplasticity,” Abbott says. “We are trying to normalize the brain.”

People exposed to the highest electric fields have very large hippocampal volume increases, Abbott says, but that is often associated with cognitive impairment. “We think that a sweet spot exists for ECT dosing and related hippocampal volume change,” he says. “It’s the dose for the perfect antidepressant response with no cognitive impairment.”

Because the study involves human subjects, this new approach to delivering ECT requires modifying the equipment that controls the current. The team has received an investigational device exception from the Food and Drug Administration for that purpose, Abbott says.

ECT currently benefits 60 to 70 percent of those treated, and the new method promises to help additional patients, Abbot says. “To see people respond, especially the very severely depressed – it never gets old,” he says. “I’ve been doing this for 12 years. It never ceases to be a jaw dropper when you see it work.”

But the real credit is due to patients who are willing to participate in the study, he says.

“These are really severely depressed individuals,” Abbott says. “It’s people at their worst. I’m really fortunate to work with patients who are struggling, but who are ready and able to help with this kind of research.”