Preparing for Disaster: UNM Hospital Participates in Region-Wide Emergency Training

Pandemic Puzzle

UNM Scientists Want to Know Why Some Groups Experience More Severe COVID-19 Symptoms

In May 2020, as growing numbers of COVID-19 patients were being admitted to The University of New Mexico Hospital, D.J. Perkins and his colleagues launched a study to try to figure why some patients got much sicker than others.

Each patient enrolled in the study had nasal or nasopharyngeal swabs taken on seven different days over a two-week period to measure the viral load in the upper respiratory tract. On each occasion, a blood sample was also taken and assayed for the presence of virus and the immune response.

Now, after enrolling 365 patients (and counting), the study has received $2.3 million in grant funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease – and a sharper focus.

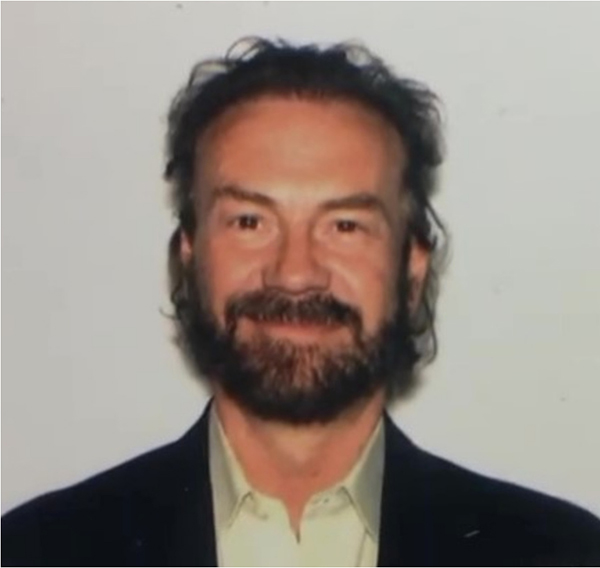

“One of the things that we witnessed in our hospitalized patients is that there was an over-representation of patients who were American Indian/Alaska Natives,” said Perkins, professor and director of the Center for Global Health in the UNM School of Medicine. “That really formed the epicenter of the grant . . . to figure out how different ancestral groups in New Mexico respond to the virus and how that impacts on their disease severity.”

At UNMH, which treats patients from across the Four Corners region, 47% of COVID-19 patients enrolled in the study were American Indian/Alaska Native, Perkins said. And in New Mexico, adjusting for population size, they have a 3.3-fold risk of infection, a 7.9-fold rate of higher hospitalization and 10.6-fold higher age-adjusted mortality rates.

Some patients in the study recovered so quickly they were discharged before the 14-day data collection period was up, Perkins said, while others remained hospitalized for longer, and some succumbed to the disease.

We are uniquely positioned to address important gaps in knowledge about the molecular basis of increased COVID-19 disease severity and mortality in disproportionately affected ancestral groups

New Mexico’s ethnic and racial diversity offers certain advantages for the study, Perkins said. “We are uniquely positioned to address important gaps in knowledge about the molecular basis of increased COVID-19 disease severity and mortality in disproportionately affected ancestral groups.”

Taking multiple samples over time enabled the researchers to paint a picture of viral load dynamics – the speed and effectiveness with which the body responds to a viral infection. The team hopes further analysis will reveal which genes put people at greater risk for severe disease, Perkins said.

Each blood sample collected in the study was analyzed for its transcriptome – an RNA readout of the genes that are expressed. “That allows us to look at how viral loads, both in the upper respiratory tract and in circulation impact the immune response,” Perkins said.

“We use software algorithms to put those genes that are differentially expressed into different informatic pipelines, so you can find signals that differ between severe and non-severe disease,” he said. “Once you identify those signals, those become therapeutic targets for new treatments for COVID-19.”

As analysis reveals these unique gene pathways leading to severe disease, “you can then go and look for FDA-approved drugs for other disease that might target those genes and gene networks,” he said.

Creating a clearer picture of who is at greatest risk for severe disease and mining the data for clues regarding potential therapies has its own rewards, Perkins said. “I am hopeful we can have a positive impact on the COVID-19 challenges in New Mexico.”