Preparing for Disaster: UNM Hospital Participates in Region-Wide Emergency Training

Rural Rescue

UNM EMS Medical Direction Consortium Takes on the Challenges of Providing Medical Guidance for Navajo Nation First Responders

Providing emergency medical services on the Navajo Nation – which straddles three states and is a bit larger in land area than the state of West Virginia – is a formidable undertaking.

Ambulances may take more than an hour to reach a patient, often after having traversed poorly maintained dirt roads, and cell phone service is spotty, at best. Then comes the long ride to an emergency room.

But the task has gotten a little easier, thanks to an agreement reached earlier this year with The University of New Mexico EMS Medical Direction Consortium, says Chris Kescoli, manager of the Navajo Nation Department of Emergency Medical Services.

“We’re very fortunate to have them on board,” Kescoli says. “The efforts that were put in place for EMS medical direction have been a tremendous help to our organization.

Prior to the partnership with UNM, each of the department’s 13 field offices had its own agreement with a local hospital or clinic to provide medical guidelines on how best to care for patients in the field, which sometimes led to inconsistent treatment standards.

Now, he says, “We have a uniform treatment guideline that was established by the UNM EMS Consortium. It’s something we’ve been needing for quite some time.” In addition, ambulance crews have 24/7 access to an on-call UNM physician to answer any questions they might have.

Having multiple medical directors meant the Navajo Nation field offices had varying access to medications and followed divergent treatment protocols, says Chelsea White IV, MD, professor in the UNM Department of Emergency Medicine and director of the UNM Center for Rural and Tribal EMS.

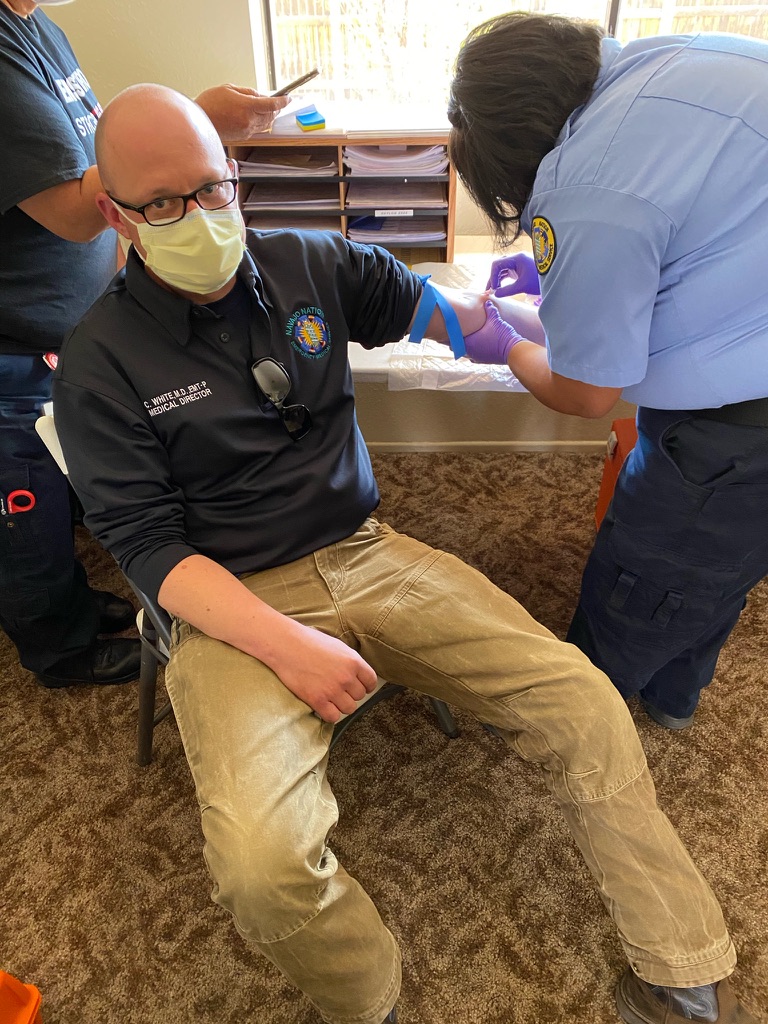

“This is much more of a coordinated, cohesive approach to EMS care in the Navajo Nation that really wasn’t there before,” says White, who along with colleague Elizabeth “Libby” Melton, CNP, spends much of his time on the road visiting field offices – sometimes responding to emergency calls along the way.

This is much more of a coordinated, cohesive approach to EMS care in the Navajo Nation that really wasn’t there before.

“It’s really exciting to be here working on this problem – basically trying to bring standard medical care to an area that is extremely remote, but is also sadly very used to not having that level of service,” White says. “It is a challenge, but it’s a fun challenge, and we’re very lucky to be able to work with so many dedicated EMS providers who have been working under these conditions for, in some cases, decades."

EMS services operating in remote rural and frontier settings face unique obstacles compared to their counterparts in cities and suburbs, White says. “It can take a long time for a sick or injured patient to get to where they need to go just because of the geography,” he says.

UNM provides medical direction for many rural New Mexico communities and pueblos, including Laguna, Acoma, Isleta, Jemez and Santo Domingo, White says. It also contracts with Sandoval County EMS, which covers the pueblos of Zia, Santa Ana, Sandia and San Felipe, as well as Pine Hill/Ramah, a non-contiguous part of the Navajo Nation.

“We do have a protocol set that covers many of them,” White says. “We’re working to streamline those. Some of what we do is move them toward what we feel are best practices. Eventually it would be our goal to have the same medicine being practiced everywhere.”

The Navajo Nation’s EMS department answers about 36,000 calls for service each year, he says. There is no centralized EMS dispatch system, with emergency calls being routed through police dispatchers who aren’t trained in medical dispatch protocols. “That is a huge issue we are working on,” White says.

An additional complication comes when responding to older patients who may not have fluency in medical English, White says. “That can be challenging. It is very helpful when on a callout in the field to have a Navajo speaker on the crew.”

Kescoli says that the challenges of providing care in a rural environment also bring unexpected rewards, especially during the long ride to the hospital after a patient is picked up.

“We’re one of many rural EMS services that spend a lot of time with patients,” he says. “It can be very different than someone who is a provider in an urban area. We have the ability to get to know the patient. If they’re stable, we’re carrying on a normal conversation. We’re doing a lot for them just to get them to where they eventually need to be for a higher level of care in an ER.”

Kescoli credits White and Melton with building relationships during their frequent site visits to the EMS field offices.

“It’s good because they’re not only becoming familiar with the Navajo Nation, but the providers are becoming familiar with them,” he says. “It’s always good to see the face of who your medical director is. It’s good to get our doctors out there to see the challenges – why it is taking us an hour to get to the hospital.”