U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy recently released his Framework for Workplace Mental Health and Well-Being, underscoring the connection between the well-being of workers and the health of organizations.

The framework makes a strong case for prioritizing the employee welfare, laying out five essentials to help workplaces become engines of well-being, providing employees with the resources and they need to thrive.

The surgeon general doesn’t actually issue a whole lot of advisories, so, it’s a big deal that the surgeon general released an advisory on this

“The surgeon general doesn’t actually issue a whole lot of advisories,” says Elizabeth Lawrence, MD, chief wellness officer in The University of New Mexico School of Medicine. “So, it’s a big deal that the surgeon general released an advisory on this. By design, it was released at the same time as the National Academy of Medicine’s Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being, and the principles are very similar.”

While the framework addresses workplace needs that were present before the COVID-19 pandemic, Murthy acknowledges that along with the unprecedented challenges everyone has faced since March 2020, there is “an unprecedented opportunity to examine the role of work in our lives and explore ways to better enable all workers to thrive within the workplace and beyond.”

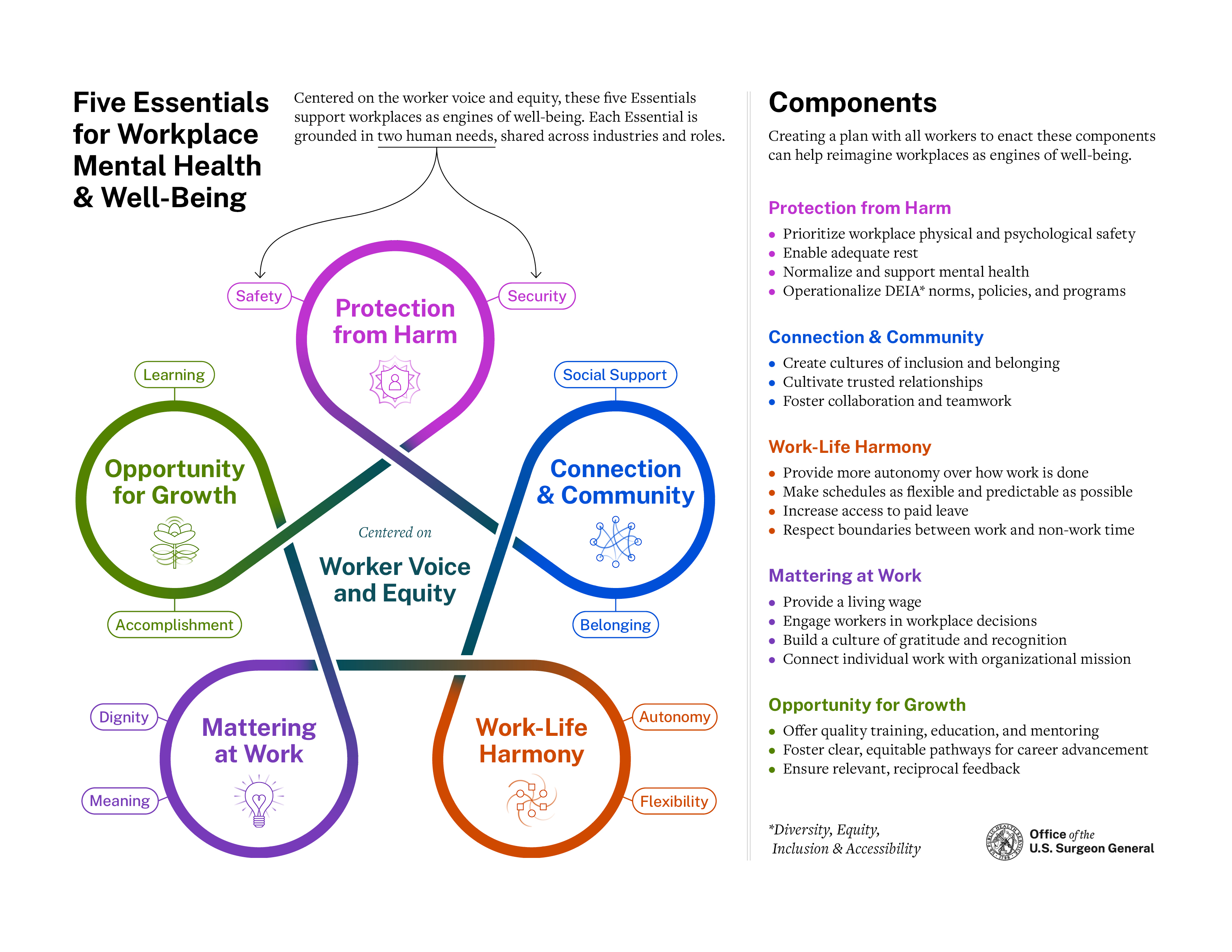

Centered around worker voice and equity, the framework covers five essentials to help workplaces become engines of well-being, providing employees with the resources and support they need to thrive.

The five essentials are Protection from Harm, Work-Life Harmony, Mattering at Work, Connection & Community, and Opportunity for Growth. This graphic provides a succinct overview of what each of these areas entails.

The interactive website is designed to spur employers into action, offering not only the in-depth report, but also Reflection Questions for each essential, and a Resources page that includes examples on how organizations like Kent State University and 9-1-1 Dispatchers are starting to implement the framework.

According to the Surgeon General’s framework, workers are struggling internationally, and conditions are getting worse instead of better.

Across the globe, workers reported feeling more stressed in 2021 than they were in 2020. In a separate 2021 survey of 1,500 U.S. adult workers across sectors (for-profit, nonprofit and government), 76% of respondents reported at least one symptom of a mental health condition, an increase of 17 percentage points in just two years.

While the pandemic did not create these work conditions, it worsened many of them. As life and work collapsed into each other and work moved to a virtual environment, it became harder to decompress due to the constant access to work. It might be convenient in terms of commute and avoiding contagious viruses, but too much merging of work and home environments can be detrimental to households.

“It’s important to factor in the impacts on child health,” says Kristina Sowar, MD, associate professor in the UNM Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences.. “For kids and teenagers, COVID has had a significant impact on their mental health, which has a ripple effect on families.”

Also, according to studies cited in the framework, rates of anxiety, depression, social isolation, job burnout and insecurity related to food, housing and income rose between March 2020 and mid-2022.

Some other stark statistics included are that nearly 80% of workers report that their workplace stress affects their relationships with friends, family and coworkers, and only 38% of those who know about their organization’s mental health services would feel comfortable using them.

“We’re starting to get a deeper understanding of what these five elements truly mean to workers,” Sowar says. “How these different dimensions provide an anchor for people to feel good in their workplace.”

The framework takes concepts like “work-life balance” and elevates them to things like Work-Life Harmony, which goes beyond the basic tenet of equally prioritizing the demands of our work and personal lives, focusing instead on our ability to successfully integrate work and non-work demands, and how that harmony is contingent on a worker’s autonomy and flexibility.

“With the concept of harmony (introduced),” Sowar says, “it isn’t about having a set number of hours on or off work. Instead, flexibility is key. Studies point to flexibility being more important to workers than their total number of work hours. Having the opportunity to take leave and decompress when they need it, to have that boundary of really being able to shut off when they’re outside of work – when those pieces aren’t present, it contributes to burnout and people feeling like they don’t have control over their lives.”

Echoing the framework, both Lawrence and Sowar emphasize that it is important that leaders support de-stigmatization of seeking mental health care,and engage workers in workplace decisions.

“As a colleague of mine used to say, ‘Nothing about me without me,’” Lawrence says. “Leaders really have to role model and share their own experiences (with seeking care), whether that’s, ‘I used to see my therapist once a month and now it’s once a week,’ or even, ‘I was really burnt out and needed to take a week off.’ To normalize these conversations, to normalize taking time off- to say, ‘I’m going to miss that meeting Friday afternoon because I have a colonoscopy.’ Otherwise, you have to hide that you’re a person who has needs. We have to role model acceptance that we’re all humans with needs.”

The five essentials coexist in the framework for a reason. They are not components that can be addressed in silos,but must be examined as a parts of a cohesive whole.

“Actively promoting an inclusive environment, talking about psychological safety, making these more open conversations is crucial,” Sowar says. “Brainstorming around how people can feel like they have more control over their work and lives. Figuring out- even as teams – how to provide support on coverage and making it less stigmatized to take space for things outside of work.”

Turning our workplaces into spaces the nurture and support the well-being of workers cannot be done without particular attention to diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility (DEIA).

When it comes to DEIA, Sowar says, “If it isn’t explicitly highlighted and made a priority, how do you shift organizational practices to honor that? How will you provide additional support for those who are underrepresented or marginalized in the workforce? The basics aren’t enough anymore, we have to go above and beyond.”