A quiet Monday morning in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) at The University of New Mexico Children’s Hospital signals a break from an unprecedented wave of severe respiratory infections in New Mexico children.

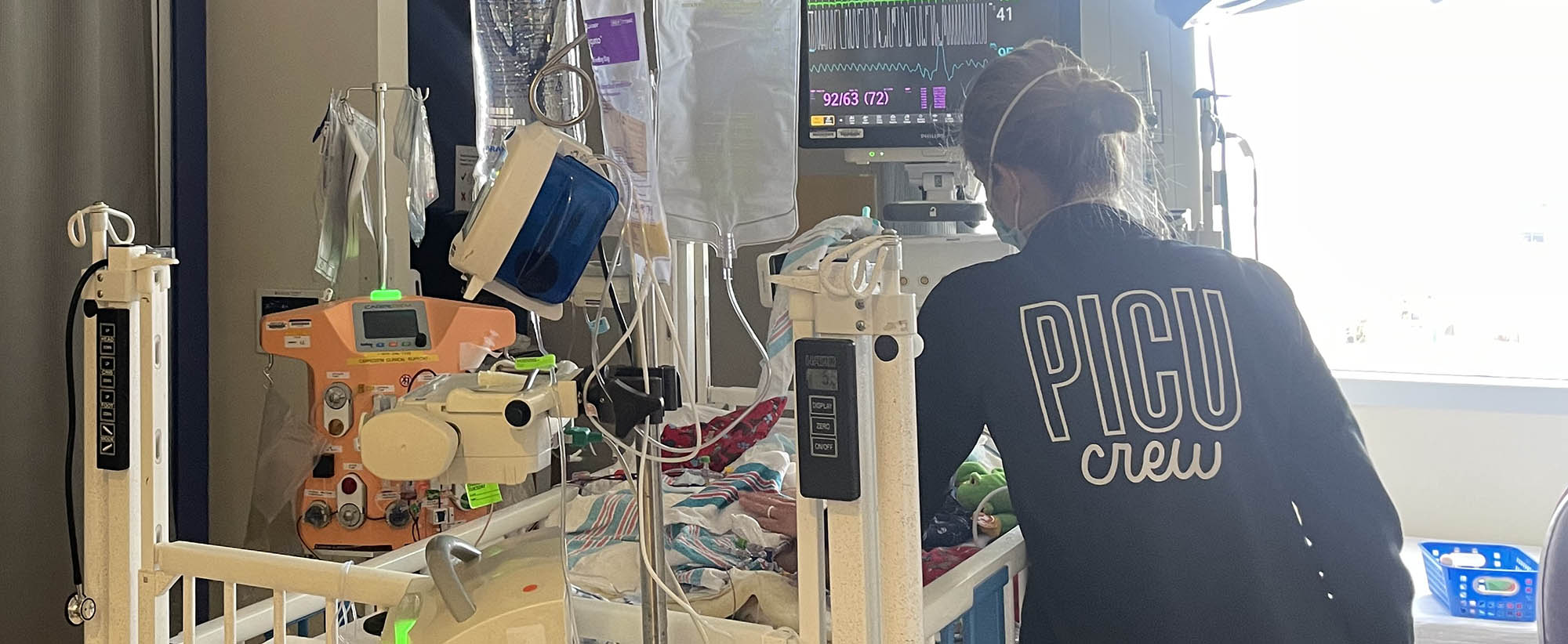

There’s a palpable heaviness as PICU nurse Jessica Boinoff sits in an empty patient room and describes the ordeal. “It’s been surreal,” she said.

What happened over the past few months was unlike anything she and her team had experienced before.

“We had healthy children with no issues at all needing to go on artificial lungs and extended periods of intubation,” Boinoff said. “We've had a lot of children die. And just feeling the pain, the psychic pain of the parents, has just been very overwhelming.”

At the height of the surge, the PICU was above capacity as hospital staff struggled to keep up with the overflow of young patients.

It came upon us very quickly. We opened up a 12-bed respiratory care unit and nursery and had patients doubling up in ICU rooms and doubling up in patient care rooms

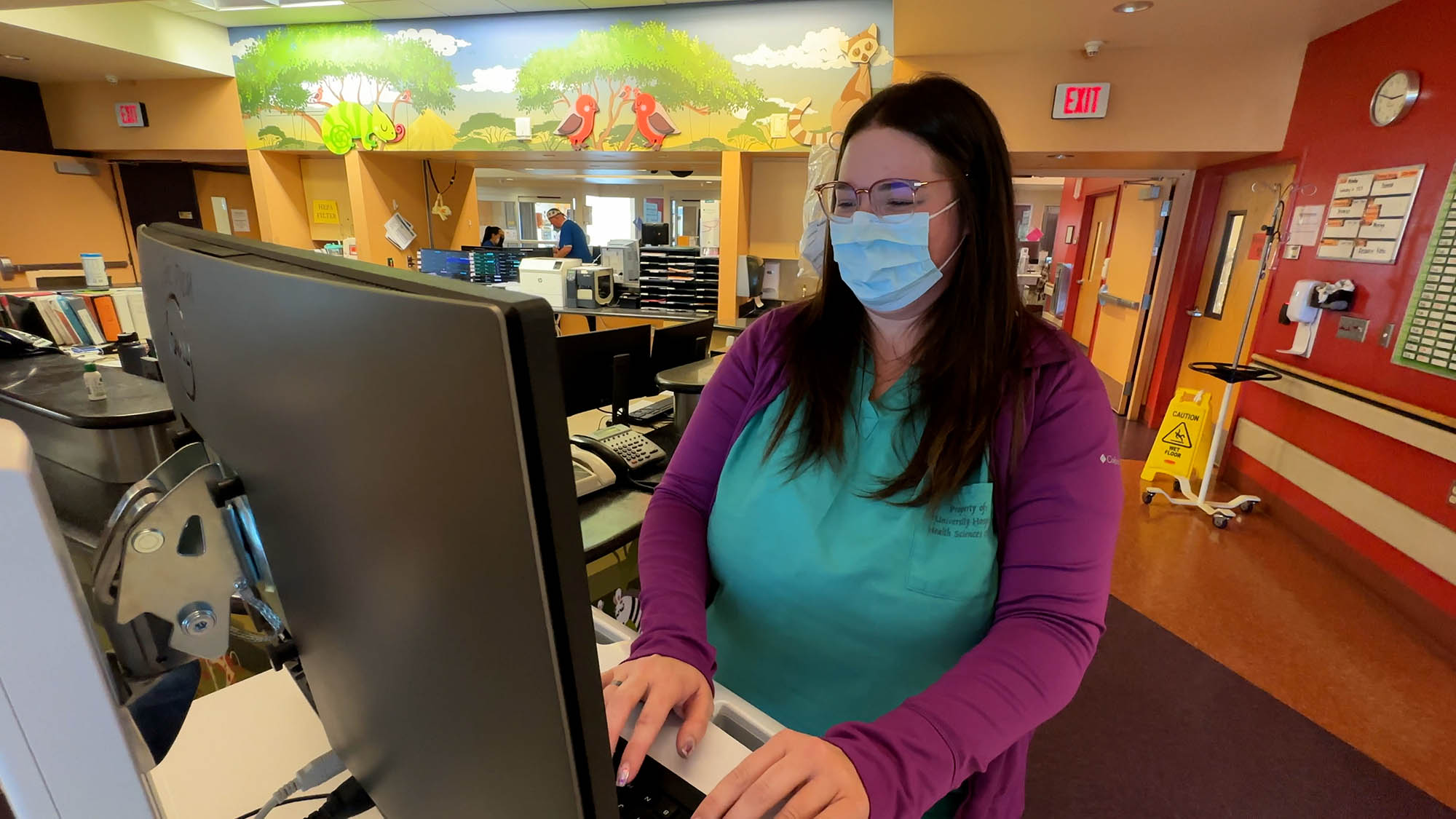

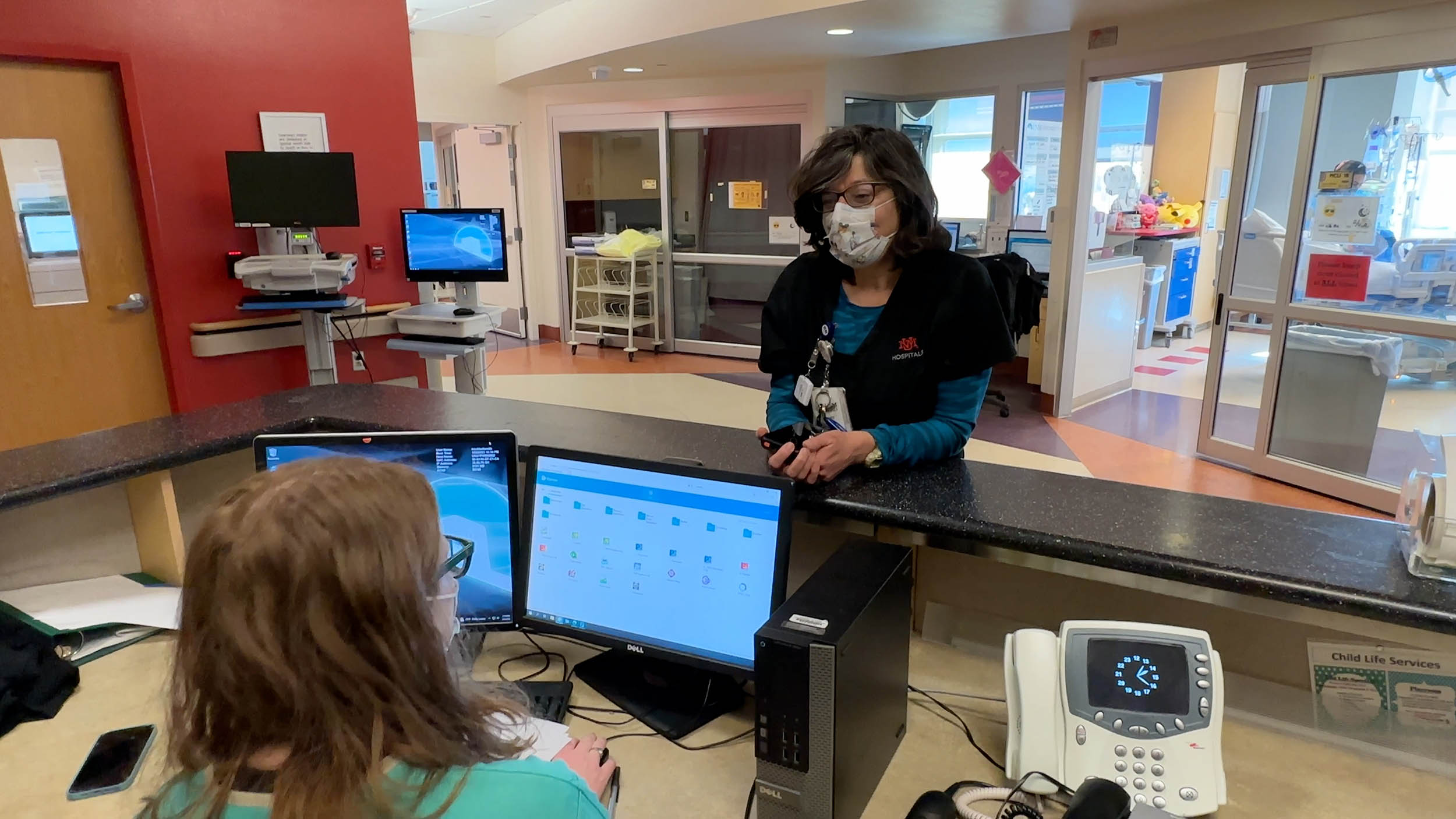

“It came upon us very quickly,” said Maribeth Thornton, PhD, MBA, RN, associate chief nursing officer of UNM Women’s and Children’s Hospital. “We opened up a 12-bed respiratory care unit and nursery and had patients doubling up in ICU rooms and doubling up in patient care rooms.”

At one point, UNM Hospital asked a federal task force for help in managing the influx of children with respiratory illnesses, especially respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

“Oh my gosh, I'd never seen that many kids at one time be that sick,” said Ashley Kam, RN, who is on a team that places patients on heart-lung bypass using an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) device. It allows the heart and lungs to rest and is typically used on adults during surgery, but during the peak of RSV, some children needed it.

Kam found herself in the difficult position of trying to reassure parents. “For parents of small children, this can be terrifying, especially when your kid’s already sick enough to need to be in the ICU,” she said.

Boinoff also did what she could to help frightened parents.

“You see the panic in their face. And you have to reassure them that we're all doing what we can and this is part of a disease process that is unpredictable at times,” she said.

That unpredictability could be heartbreaking for both parents and the nurses who tried everything they could to make a difference.

“You feel numb when you find out that your patient died a couple of days later – where you thought maybe they would turn a corner and they weren't able to do that,” Boinoff said. “You feel like you have some ghosts that you're carrying with you. There's no other way to say it."

To get through it, the PICU nurses relied on each other.

“You’re checking up on them and knowing that they're checking up on you,” Boinoff said of her coworkers. “Being there to hold them, and just say, ‘Hey, that was a rough day.’”

“I always felt like when I came to work I was just trying to be positive,” Kam added. “I was trying to support people, trying to go above and beyond for one another.”

Often, the inspiration they needed came from their littlest patients’ strength.

“They're very strong. When you have a baby that is intubated and then they're feeling better, now they're like a regular baby. You can be silly and they're going to clap their hands, and they're going to laugh,” Boinoff said.

Through the highs and lows, the one constant was – and continues to be – the dedication of the team at UNM Children’s Hospital.

“It’s a real honor to be with a family and a patient when they're going through something extremely difficult,” Boinoff said. “You can try to make it less awful for them by being compassionate, by being helpful, by being supportive. And that's a gift – it's a gift for us.”