When we hear the word ‘metabolism’ we tend to think of how quickly or slowly a person’s body “burns fat.” Is my metabolism high or low, doc? How can I increase my metabolism?

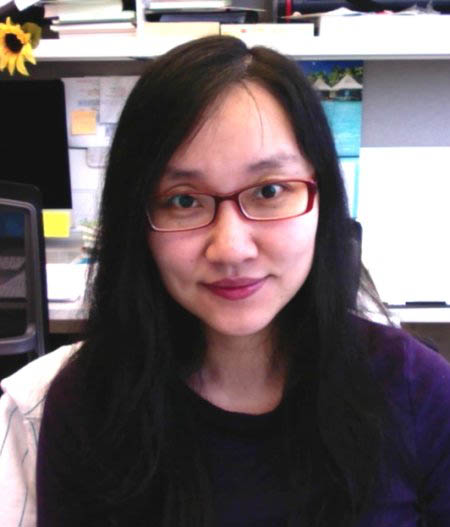

Jing Pu, PhD, defines it more precisely: “The chemical processes that occur within a living organism in order to maintain life.” For Pu, an assistant professor in the University of New Mexico Department of Molecular Genetics & Microbiology (MGM), the study of metabolism goes above and beyond maintaining life, and into the realm of how to improve a person’s quality of life through better screenings and treatments.

As the recipient of an R35 grant through the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Pu studies metabolism at the molecular level through the lens of fatty acids and how they contribute to lipotoxicity, a major signifier of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Type 2 diabetes and other metabolic disorders.

“Lipotoxicity is a kind of toxic effect caused by overloaded fatty acids, which can cause inflammation, membrane damage [and] cell death,” Pu says. “In our research we’re trying to understand the fatty acid transport with cells under normal and pathological conditions and how we can avoid exposing extra fatty acids to the cells.”

Pu’s work is basic science, meaning it doesn’t directly translate into patient care, but she believes in basic science as the essential, foundational work that is required for translational research.

My hope is that we identify the key molecules in the metabolic processes, understand the mechanisms of how they work, and then we can tell whether the molecules are suitable or not suitable as drug or treatment targets

“My hope is that we identify the key molecules in the metabolic processes, understand the mechanisms of how they work, and then we can tell whether the molecules are suitable or not suitable as drug or treatment targets,” Pu says. “If they are, we can collaborate with other experts and help each other in the development of therapies. And I think it will happen.”

Pu’s career in academia spans the globe. After getting her PhD in cell biology in Beijing, Pu went to the NIH for her postdoctoral training in cell biology before landing UNM. She first received funding support through the UNM Autophagy, Inflammation and Metabolism (AIM) Center.

After completing three years (“Well, two years and seven months,” laughs Pu) of the grant cycle through AIM, Pu received independent funding support for her own lab research in the form of an R35 NIH grant. In an R01 grant, the researcher must specify a set of goals that they then adhere to throughout the grant cycle.

“But in an R35 grant,” Pu says, “you have more flexibility. You don’t set specific aims, and you can follow new research directions as opportunities arise, which could be very important to an early-stage investigator.”

In addition to fatty acid metabolism, Pu’s lab explores cholesterol transport and regulation related to COVID-19. In this work Pu collaborates with virologist Alison Kell, PhD, looking at how the infections can cause cholesterol transport defects, and how that in turn will impact cholesterol homeostasis.

“We’re also collaborating with other people working on protein structures, putting all the data together in order to apply for an R01 grant to support our continued, collaborative research,” she says.

Pu wants to emphasize the collaborative nature of her research by acknowledging the people she works with, both at UNM and beyond.

In the fatty acid work, Pu is joined by UNM colleagues Meilian Liu, PhD, Eric Prossnitz, PhD, Eliseo Castillo, PhD, and Karlett Parra, PhD, along with Jiandie Lin, PhD, from the University of Michigan. In Pu’s cholesterol research she works with UNM colleagues Kell and Yi He, PhD, along with Dartmouth’s Michael Ragusa, PhD.

All of these researchers are trying to solve a fundamental problem, in that scientists don’t know how a lot of molecular mechanisms happen.

When thinking about the future, Pu’s biggest hope for her work in basic science is to develop a foundation that will help inform and impact translational science, giving other researchers the tools and data needed to create treatments and therapies for patients.

“I always tell my students and trainees – maybe you feel it’s too far away, and you can’t see how our work is important, but trust me that sooner or later, when we understand the basics and how these things happen, the impact won’t be far away anymore,” Pu says.

Joining UNM as a junior faculty member in 2019, Pu admits she was “kind of a naïve postdoc.” At the NIH, she wasn’t able to obtain much training about how to write grants to secure funding, a skill that Pu quickly realized is essential for research faculty.

“Our department (MGM) and the AIM Center gave me a lot of support,” Pu says. “I had three mentors helping me. Without all that support, I’d probably still be struggling to figure out how to get funding from the NIH. I’ve learned a lot in the last three years.”

Pu’s introduction to UNM also quickly overlapped with the start of the pandemic, making her learning curve and continuing her work more difficult than expected. With two young kids, there’s one more shoutout Pu can’t overlook.

“The pandemic took away a lot of daycare support,” Pu says. “A lot of facilities closed, or they wouldn’t take new kids, so we really didn’t know what to do. And then my husband gave up his own job opportunities to stay home to take care of the kids for three years. He’s a huge supporter of my career. I'm so thankful, I think I’m so lucky to have this family.”