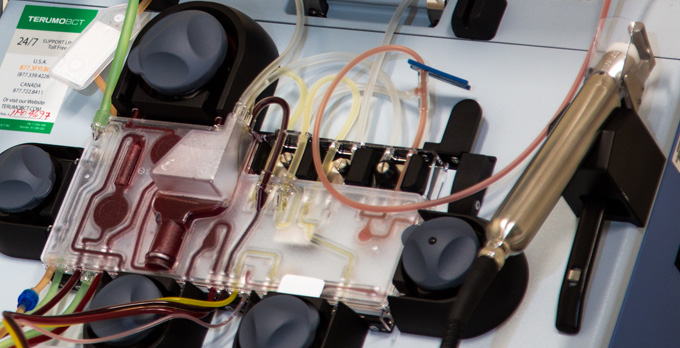

A patient undergoing treatment for chronic kidney disease typically spends three days a week at a clinic with needles in their arm, lying still for up to four hours at a time as a dialysis machine filters waste products and excess fluid from their blood.

Not surprisingly, about one-quarter of dialysis patients are diagnosed with depression, which in turn may lead to impaired motivation, making it harder for them to comply with their treatment regimen.

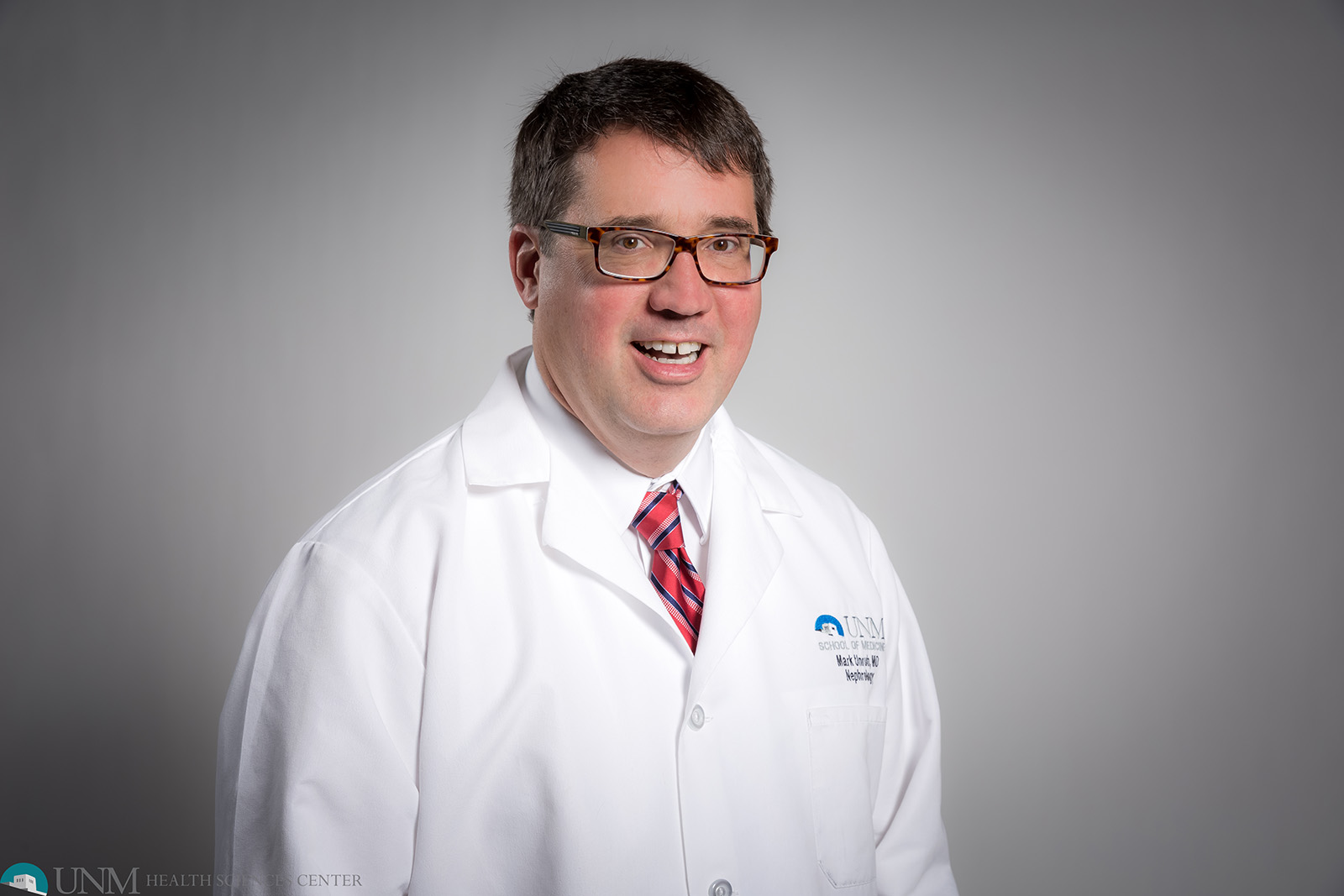

“If you look at the outcomes of people who are depressed on dialysis, they’re challenging,” said nephrologist Mark Unruh, MD, chair of The University of New Mexico’s Department of Internal Medicine. “Their quality of life is lower, adherence is poorer and hospitalization and mortality is higher.”

A few years back, Unruh and colleagues at the University of Washington and the Rogosin Institute conducted the ASCEND study, which compared treatment by a provider using cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a course of sertraline (an SSRI medication sold under the brand name of Zoloft).

There’s a lot of overlap between symptoms of kidney failure and depression.

In a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 2019, the researchers found CBT and sertraline were about equally effective in treating depression symptoms, providing relief to some 40 percent of patients who participated.

Now, the study results are being translated into a real-world intervention, supported by a $2.1 million implementation grant from the federally funded Patient-Centered Outcomes Institute (PCORI).

About 8,350 patients of Satellite Healthcare, which provides dialysis treatments at 87 centers in seven states, will now have ready access to depression care. “They’re taking our educational interventions, checklists, metrics and putting it into their usual processes,” Unruh said.

More than half a million people nationally are undergoing dialysis at any given time (including 4,000-5,000 in New Mexico), he said. Implementing these strategies for managing depression within Satellite’s dialysis units paves the way for other dialysis providers to follow suit. Just eight organizations provide care to 90 percent of patients in the U.S.

“You do these studies and you publish the papers and nothing happens, usually,” Unruh said. “With PCORI there’s a pathway for the study to be applied through dissemination grants and implementation trials. It’s touching as many people as possible. Basically, you’re taking what you did and applying it really broadly.”

The original study recruited 184 patients at 41 dialysis facilities in three U.S. metropolitan areas, 120 of whom completed a 12-week treatment regimen. The idea of providing point-of-care depression treatment to patients reflects a growing trend toward treating the whole patient in dialysis care, Unruh said.

The connection between dialysis and depression “is incompletely understood,” he said. “There’s a lot of overlap between symptoms of kidney failure and depression.” But until now the problem has not been studied in depth.

Next, he and his partners want to secure funding for the next phase of research. “I’d really like to have an answer for the 60 percent of people that don’t get better” using standard treatments, Unruh said.

With the advent of new drug therapies for depression, he is optimistic about finding ways to help additional dialysis patients. “For depression it’s a really exciting time, with really new therapies for the first time in a long time.”