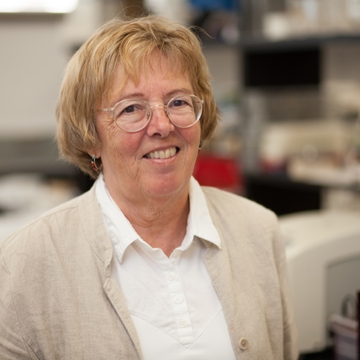

Last December, University of New Mexico neuropathologist Elaine Bearer, MD, PhD, was methodically studying brain tissue samples from two deceased dementia patients when she noticed something peculiar.

“I'm seeing these things in the microscope that I can't figure out what they are,” recalled Bearer, Distinguished Professor in the UNM Department of Pathology and director of the neuropathology core for the UNM Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). “They're strange brown lumpy things.”

It was the prologue to a scientific detective story.

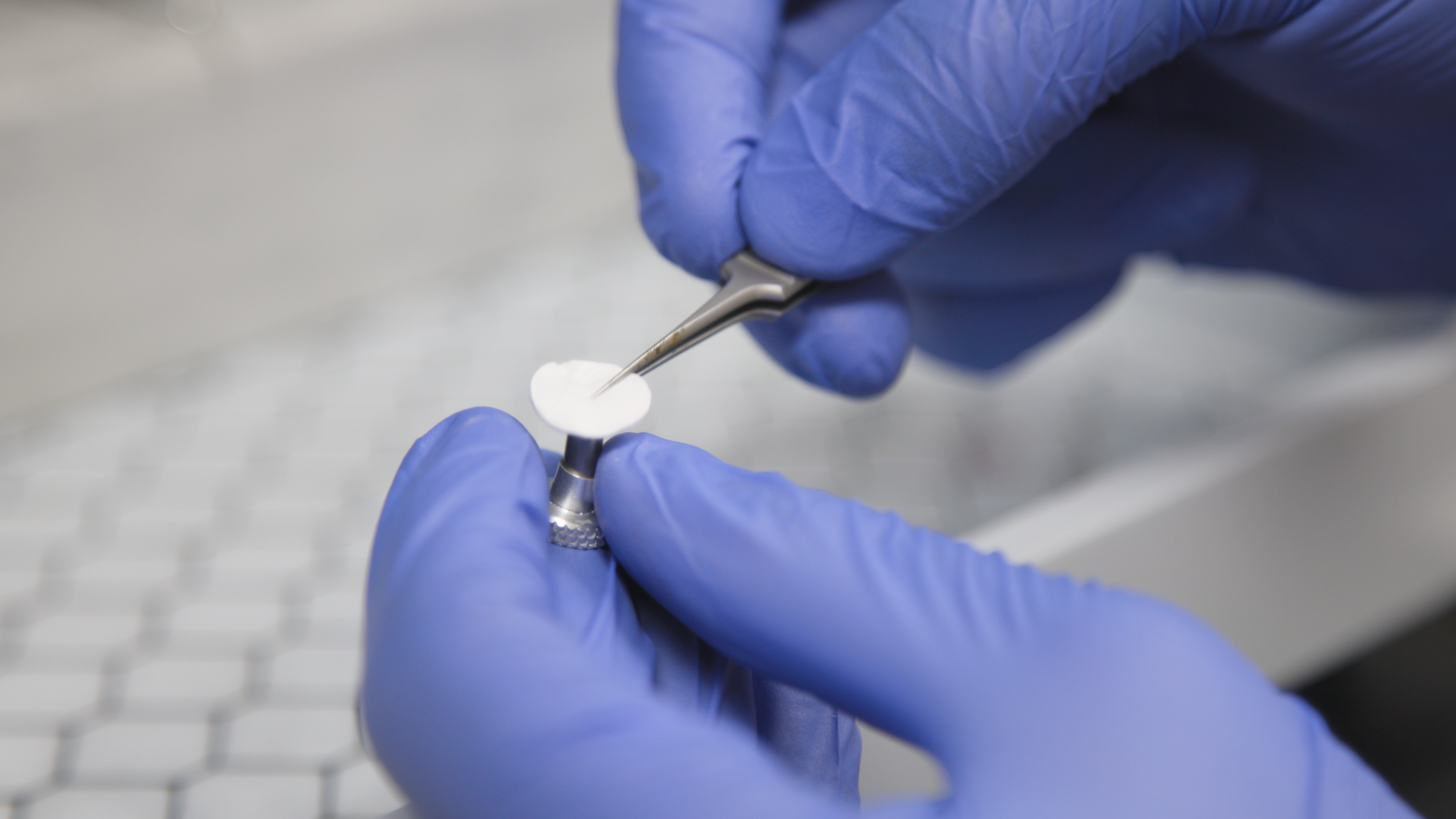

Pathologists typically use a variety of stains to highlight and classify microscopic structures in tissue, but these tiny blobs resisted identification, Bearer said. Then a colleague – Natalie Adolphi, PhD – suggested that she send the samples to Matthew Campen, PhD, a Distinguished Professor in the College of Pharmacy, who has found a way to extract and quantify the microplastics in human tissue.

Microplastics are formed when plastic is degraded and broken down over the course of decades, often through exposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays in sunlight. Scientists report that microplastics are now so ubiquitous in the environment that they have found their way into the food chain – and into the human body.

Campen’s lab has documented substantial amounts of microplastics in human brains stored in tissue repositories. But when postdoctoral fellow Marcus Garcia, PharmD, RPh, tested the tissue from the brains of the dementia patients Bearer had been studying, he isolated about 20 grams of plastic – many times the amount in “normal” brains.

Now she knew that the two dementia patients – one of whom had Alzheimer’s and the other who suffered from a condition known as Binswanger’s disease – had excessive amounts of plastic in their brains. ADRC director Gary Rosenberg, MD, had followed the male Binswanger’s patient for seven years prior to his death.

“The first thing I did was I took some of the purified plastics from the Binswanger’s case and I did electron microscopy on it,” Bearer said. “They don't look like the same plastics that Matt is getting. They're different, they're a different shape. They actually have a different chemical composition.”

She still couldn’t identify the brown spots she had seen under the microscope but she had a hunch.

“It’s very interesting that there's a lot more plastics in these demented brains than we found in normal brains. I wanted to know if those brown deposits were the plastics, but there wasn't any way to stain it specifically for plastics.”

During a brief sabbatical at the California Institute of Technology in September, Bearer used a confocal laser scanning microscope to study purified samples of the plastics Campen’s team had isolated. She exposed the plastic particles to 10 lasers that emitted a broad spectrum of wavelengths of light and finally found one that caused them to fluoresce, so that they emitted light at a slightly longer wavelength.

Back in New Mexico, she re-examined the brain tissue samples while illuminating them with the same wavelength and found that the brown spots in the tissue fluoresced, confirming that they were bits of microplastic.

Bearer, who with Campen and Adolphi published a preprint of a paper documenting her findings on the Biorxiv site on Nov. 27, has been sharing her discovery with peers and recently presented her findings at a Society for Neuroscience meeting and has submitted a paper for publication in the journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

“I've now talked with four other neuropathologists across the country,” she said. “I showed them my pictures and they said, ‘Oh my God, I've seen these, too. I saw them in my specimens and I couldn't stain them. I didn't know what they were.’ Then I showed them that they’re plastics, and they go, ‘Of course.’”

Bearer’s findings, coupled with those from the Campen lab, raise intriguing possibilities. Could an excessive accumulation of plastics in the brain trigger dementia symptoms? Or, are people with dementia pathology less able to clear microplastics from the brain, leading to a build-up?

Bearer says it’s too soon to tell. “I don't have enough samples to do any kind of statistics, and I can't say – because I'm only looking at dead people – I can't see the plastic as causative.”

Going forward, she hopes to examine additional brain tissue from patients enrolled in ADRC studies to learn more about where the microplastics are most prone to accumulate. She also holds out hope for being able to diagnose dementia pathology in living patients using magnetic resonance imaging.

Bearer says the ADRC, which received full funding from the National Institutes of Health earlier this year, brings new resources to bear for dementia patients in New Mexico and provides a venue for UNM Health Sciences researchers to collaborate across disciplines.

“Having the ADRC means there’s funding to do things for New Mexicans that we didn’t have before,” she said. “These discoveries are coming from this constellation of experts that we’ve somehow collected here. It’s this confluence of this expertise that are coming together to address these critical questions.”

Read more about the discovery and measurement of microplastics in human brains below.

UNM Researchers Find Alarmingly High Levels of Microplastics in Human Brains – and Concentrations are Growing Over Time

Microplastics – tiny bits of degraded polymers that are ubiquitous in our air, water and soil – have lodged themselves throughout the human body, including the liver, kidney, placenta and testes, over the past half century.

Now, University of New Mexico Health Sciences researchers have found microplastics in human brains, and at much higher concentrations than in other organs. Worse, the plastic accumulation appears to be growing over time, having increased by 50% over just the past eight years.

In a new study published in Nature Medicine, a team led by toxicologist Matthew Campen, PhD, Distinguished and Regents’ Professor in the UNM College of Pharmacy, reported that plastic concentrations in the brain appeared higher than in the liver or kidney, and higher than previous reports for placentas and testes.