Steve Segura, a third-generation coal miner and native of Raton, N.M., remembers a conversation with his father after he graduated from Raton High School in 1977.

“What are you going to do now, jito (son)?” he asked me. “You going to go in the service? You want to come work in the mine?”

At the age of 19, Segura decided to join his father at the York Canyon Mine, one of the coal mines in the area around Raton, a railroad and mining town in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the Colorado border. He would follow a family legacy. His dad, uncles, cousins and grandpa were all coal miners.

At the age of 19, Segura decided to join his father at the York Canyon Mine, one of the coal mines in the area around Raton, a railroad and mining town in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the Colorado border. He would follow a family legacy. His dad, uncles, cousins and grandpa were all coal miners.

Back then, mining jobs were hard to get. They paid well, came with benefits, and could support a family and guarantee a pension after 20 years, said Segura, now 65. He worked underground for 20 years in a variety of jobs: cutting coal, hauling it out, bolting up the roof and setting timber supports to reinforce the mine shaft. “It’s just a dirty job,” he said. “You’re always in the dust.”

Segura went on to work for another 30 years as a well site mechanic at Pioneer Natural Resources in Trinidad, Colo. Once an avid hunter who could cover miles on foot during deer and elk season, Segura now struggles to breathe on short walks with his wife and while doing yardwork.

Fifty years after he began working underground, Segura has been diagnosed with Black Lung Disease, also known as coal workers' pneumoconiosis, caused by the inhalation and trapping of coal dust in miners' lungs. “My heart is good, but if you see the X-rays of my lungs, both are scarred up and black,” he said.

He is receiving care from pulmonologist Akshay Sood, MD, MPH, a professor in The University of New Mexico School of Medicine’s Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine. Sood travels to Raton monthly to see patients with Black Lung Disease and other pulmonary conditions at Miners Colfax Medical Center.

He is receiving care from pulmonologist Akshay Sood, MD, MPH, a professor in The University of New Mexico School of Medicine’s Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine. Sood travels to Raton monthly to see patients with Black Lung Disease and other pulmonary conditions at Miners Colfax Medical Center.

Sood has also served as the Miners Colfax Endowed Chair in Mining-Related Lung Diseases since the hospital established the position eight years ago. He works with the medical center’s Miner’s Outreach Services and specially trained Black Lung Program team, who travel in a specialized mobile unit to see miners in Raton and across New Mexico and the region.

“People who do mining tend to be the cream of the community,” Sood said. “They are the strongest in the community, and they are usually the leaders of the community.” These workers typically perform at 120 to 150% predicted on measures of the volume and speed of air inhaled and exhaled on lung function tests, when compared to the average person, but over time the disease process starts to erode their lung health.

“When they go down to 80% predicted, that’s still considered normal for their age,” he said. “But the difference between 150% to 80% predicted means almost half their lung is gone. That’s quite an incredible thing. When you've always been told you're tough, you don't talk about your symptoms. They do not like to be told that they can't lift, that they can’t bring wood in for the woodstove, that they can’t lift the groceries out of the car. They'll never tell you that. Their wives will tell you that. They’re the ones concerned.”

Black Lung Disease can take years to develop and progresses slowly. In early stages, the most common symptoms are coughing, shortness of breath and chest tightness. It can lead to lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the need for supplementary oxygen. It has also been found to decrease life expectancy by 12.6 years.

Segura recalled that while he worked at York Canyon Mine, he spent a month and half of working in an area where the company was drilling a hole with a giant bit to improve ventilation.

We were down there, and there was no air. You're driving a big diesel machine under there with the exhaust and coal dust. It was scary. It was ugly.

When Segura told his boss that it was hard to breathe, “He said, ‘No, no, you keep going. You're all right.’ And you try to use the respirator, but it gets so dang hot.”

It’s a familiar story in Raton, which once bustled with stores, restaurants and services that served the mining community, and there is still a dedication to its mining heritage and the health of its miners. Miners Colfax and its Black Lung Program has partnered with the UNM School of Medicine for more than 20 years to provide medical counseling, support and tests for generations of coal miners in New Mexico and has become a regional hub for people throughout the Mountain West who are at risk for Black Lung Disease.

Sood, who has been traveling to Raton for 12 years, says his work with miners combines his scholarly research and clinical practice in occupational pulmonology with his dedication to providing medical care for patients who often live in rural areas and travel long distances for care.

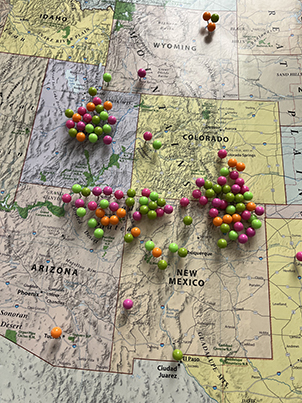

People come for care from across New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Montana and North Dakota to Raton, a town of 5,000 people. Miners Colfax is a regional center of excellence. And their association with The University of New Mexico has projected them to national leadership.

The Miners Wellness ECHO Program is another important part of the Miners Colfax Medical Center and UNM partnership.

Project ECHO, a nonprofit organization at the UNM Health Sciences Center, connects primary care providers with specialists so they can learn best practices through its telementoring model.

Its goal—to improve access to specialty care in underserved areas, including Raton—supports the in-person teamwork that Sood and the Black Lung team provide and extends a virtual community of expertise across the state and the country.

Its goal—to improve access to specialty care in underserved areas, including Raton—supports the in-person teamwork that Sood and the Black Lung team provide and extends a virtual community of expertise across the state and the country.

“What we've learned in the process of taking care of a miner is that it’s a multi-dimensional process that involves access to other professionals as well,” Sood said, referring to the lawyers, benefits counselors, home health professionals, and respiratory therapists who participate in Project ECHO. The Miners Wellness ECHO is a way for participants to learn from each other, he said.

Treating miners and others working in dangerous physical occupations in remote parts of the country has become Sood’s specialty. After receiving his medical degree at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences and a master of public health degree at Yale, Sood worked in Nevada caring for workers at the Nevada Test Site, where nuclear weapons were tested, followed by the coal mines of southern Illinois, where he first encountered Black Lung Disease.

On a recent monthly visit to Raton, Sood and the Black Lung Team at Miner’s Colfax saw four miners and four non-miners. Each miner’s chest X-ray indicated Black Lung Disease, according to Sood, who had reviewed them all before the visits. The men all had undergone a pulmonary evaluation – a physical exam, a pulmonary function test and arterial blood gas tests, which measure blood oxygen levels during strenuous exercise on a stationary bike.

These results would determine whether they qualified for miner’s monthly benefits, established by the Black Lung Benefits Act, a federal law that provides monthly benefits and medical coverage to coal miners (or their surviving dependents) who have developed Black Lung Disease as a result of their work. In 2023, the monthly benefit for a miner with no dependents was $737.90, but it can be as much as $1,475.80 per month for miners with three or more dependents.

But coal companies, who pay out the benefits, regularly dispute claims of Black Lung Disease on X-rays and in the battery of tests performed by Sood and the Black Lung team, he said. None of the four miners seen this day in Raton qualified for benefits, although, like former miner Steve Segura, they have been diagnosed with Black Lung Disease.

Although these laws were designed to favor miners, they have been weakened by disputes over whether a miner’s Black Lung Disease diagnosis is valid, Sood said. “Black Lung is a classic example of how a good law was utilized by some in a bad way to really hurt the miner instead of helping them.”

Black Lung Disease was the underlying or contributing cause of death for 75,178 miners from 1970-2016, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Black Lung Disease was the underlying or contributing cause of death for 75,178 miners from 1970-2016, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Sood advises miners come in every two years to see how the slow-moving disease has progressed and to see if their test results meet the criteria to receive benefits. In the meantime, he encourages them to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

Helping those whose ability to breathe has been compromised is a driving force behind his work as an occupational pulmonologist. For Sood, the work has a personal dimension.

“Anyone who immigrated into this country has a very distinct memory of the first day in America,” Sood said. “My first recollection was that I landed in New York City and the air was breathable. I came from Delhi, which was so smoggy. I expected to see smog, but it was clear. It was a beautiful day. I thought, ‘How could you live in a city that's bigger than Delhi and have breathable air?’ What drew me to pulmonary medicine was the ability to understand that some people in America don't have the gift of free, healthy and safe air.”

Sood, who also serves as assistant dean of Mentoring and Faculty Retention for the UNM School of Medicine, said he benefited from finding mentors during his training who saw his potential and supported his career trajectory. He credits the mentoring process as pivotal to his experience in health care and one that he wants to make available to others.

Meeting patients where they are, especially those living in rural areas where a trip to Albuquerque would mean significant expense, hours of travel and time off work, is also a goal of Sood’s and underlies UNM Health Sciences’ priority to remove barriers to care for all New Mexicans.

“The UNM Health Sciences Center has a vision of having more physicians – not only physicians – but all health care professions, so that they can deliver care in various rural communities,” Sood said. “If even one of our residents or fellows goes out and provides occupational medicine or pulmonary medicine in Raton, New Mexico, it will change the face of health care in that community. That's really what we want to do.”