Preparing for Disaster: UNM Hospital Participates in Region-Wide Emergency Training

Timing is Everything

UNM Stroke Doctors Remove Clots From the Brain Up to 24 Hours After Onset of Symptoms

Doctors who treat stroke have a saying: time is brain.

The most common type of stroke occurs when a clot blocks an artery in the brain, cutting off the supply of oxygen. The sooner the clot can be cleared and blood flow restored to the affected area, the greater the likelihood the patient will have a good outcome.

New studies show that patients have a much longer window of time in which they might benefit from cutting-edge clot-removal procedures than was previously believed to be the case.

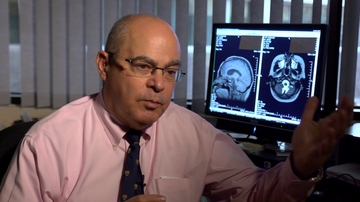

The 24/7 stroke team at University of New Mexico Hospital has already implemented the new recommendations, says Howard Yonas, MD, chair of UNM's Department of Neurosurgery.

"We've expanded the window to 24 hours," Yonas says. Until now, most doctors would not perform thrombectomy - the technical name for the extraction of a clot - after six hours, based on the assumption that too much brain tissue had been damaged from oxygen deprivation.

But new ways of measuring blood flow in the brain have shown that in many cases neural tissue is still receiving some oxygen-carrying blood, even though stroke symptoms are present.

"How does the tissue stay alive?" Yonas asks. "It stays alive because the route of blood supply is not just through that one vessel. There's a web of smaller vessels around the outside of the brain. What we've learned is for a lot of people it doesn't all block off."

Interventional radiologist Danielle Sorte, MD, is one of three UNMH physicians who perform thrombectomies. She says that despite its efficacy, the procedure is still gaining wider acceptance.

"A lot of people in the medical community have not even heard of it," she says. But studies published recently in The New England Journal of Medicine are bringing the technique to a wider audience. It is now considered a proven treatment and the new standard of care.

Decades ago, there was little doctors could do to help stroke patients. "It was this tragic, untreatable disease," Sorte says. The introduction of the clot-dissolving drug tPA in the late 1980s offered some hope, but it had to be administered soon after the onset of symptoms and worked best on clots in smaller vessels.

In the 2000s, the development of retrieval devices that could be delivered to the site of a clot via a catheter threaded through a patient's artery made it possible to remove clots from large vessels in the brain, like the middle cerebral and internal carotid arteries.

Sorte and neurosurgeons Andrew Carlson, MD, and Christopher Taylor, MD, provide round-the-clock coverage to treat stroke victims who, after specialized neuroimaging studies, are deemed eligible for thrombectomy. Together, they perform about 100 of the procedures a year. More than 30 percent of patients see significant recovery - a huge improvement when, left untreated, patients die or suffer severe disability.

That number is likely to climb, thanks a communications network linking emergency rooms in 18 hospitals around New Mexico with the stroke experts at UNM Hospital. UNM specialists can review CT scans of those patients and advise whether they should be airlifted to UNMH for treatment.

Meanwhile, UNMH emergency room protocols route patients with stroke symptoms to neuroimaging as soon as they arrive, with the on-call interventionalists arriving within half an hour.

"What people fear more than death is being neurologically devastated," Sorte says. "We're allowing them to live independently and have freedom of the life they have left without disability.

"It's really exciting to be working at a time when there's something that's having this big of an impact."