Preparing for Disaster: UNM Hospital Participates in Region-Wide Emergency Training

Targeting Tau

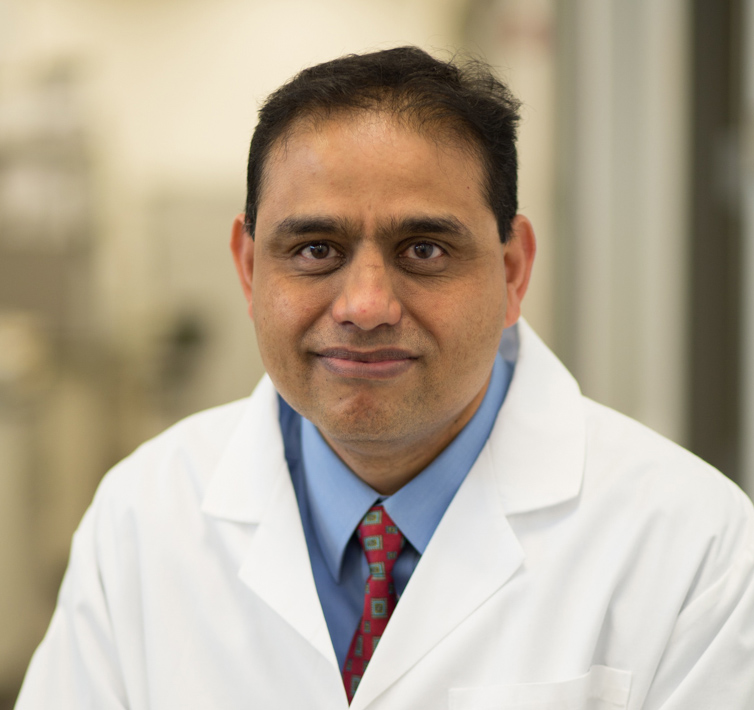

UNM Scientist Kiran Bhaskar Seeks New Alzheimer’s Treatment Methods

For decades, Alzheimer’s disease researchers have sought ways to eliminate sticky plaques of a protein called amyloid beta that build up on neurons in the brain – but drugs that do just that have little effect on dementia symptoms.

Kiran Bhaskar, PhD, an associate professor in The University of New Mexico Department of Molecular Genetics & Microbiology, has spent the past 20 years studying a different protein, called tau, which normally helps to stabilize neurons.

In the case of Alzheimer’s and a number of other neurological diseases, tau is known to accumulate in long tangles that disrupt the ability of neurons to communicate with one another, causing patients to experience cognitive decline.

Bhaskar and others think targeting it, rather than amyloid beta, may hold the key to effective treatments. In a new paper published in Cell Reports, he and his team found that a defective form of tau can trigger an inflammatory response in the brain that harms neurons.

The timing of the paper’s publication is auspicious: today is World Alzheimer’s Day, and September is World Alzheimer’s Month, Bhaskar points out.

They take care of all the debris, making sure our brain is clean.

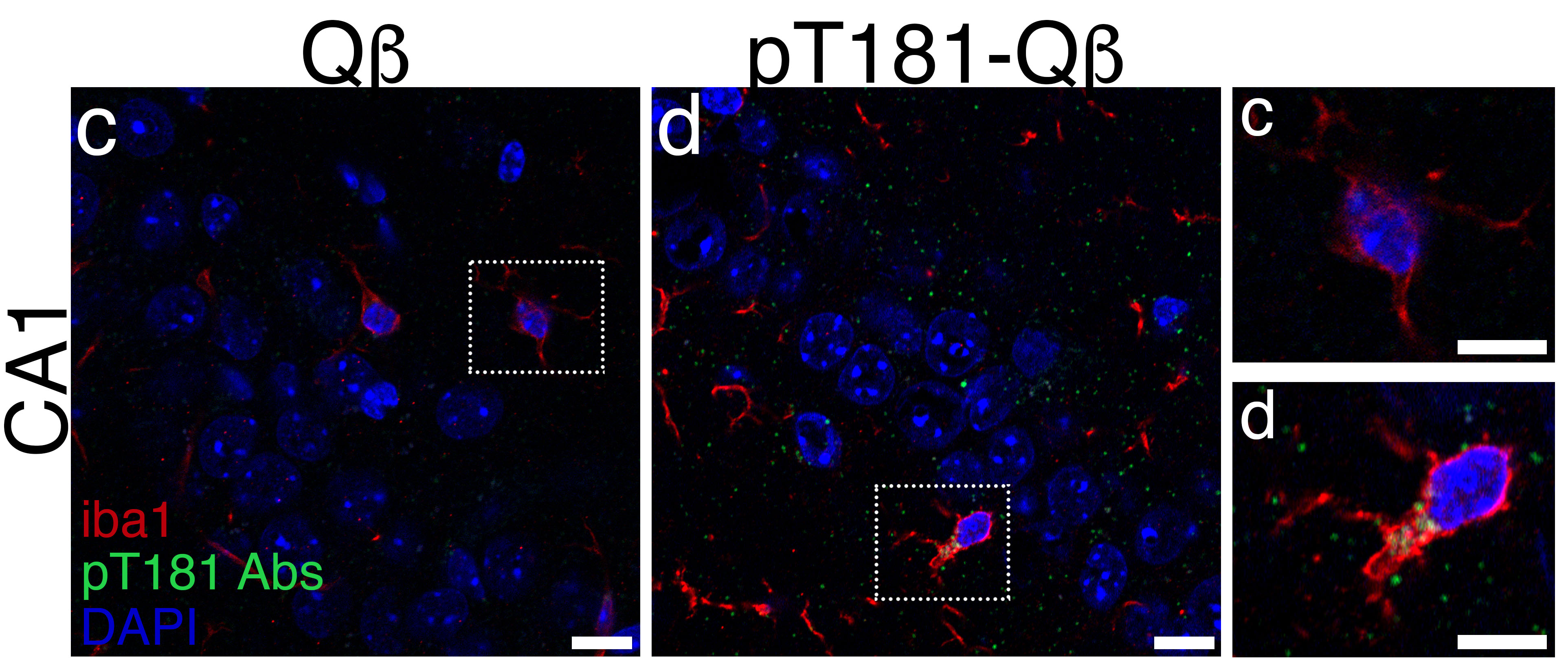

The research centered around interactions between tau and microglia – brain cells that serve an important housekeeping function by sweeping damaged bits of cells out of the body. Bhaskar liken them to trash haulers: “They take care of all the debris, making sure our brain is clean.”

But sometimes good microglia turn bad. “What happens is they can go rogue in various neurological conditions,” he says. These “rogue” microglia release chemical signals that create inflammation in brain structures.

Bhaskar wants to know why microglia go rogue in the first place. The answer may have to do with a “pathological tau,” a misfolded form of the protein. “This gunk accumulates inside neurons,” he says. “When the neuron senses tau it tries to spit it out.”

When tau is expelled from neurons into the extracellular space, the microglia mark it as abnormal and sense it as a “danger signal.”

These sentinel cells “can act like a double-edged sword,” triggering the inflammatory cascade while trying to clear cellular debris from the brain, he says. They also become less effective as we get older, he notes. “Microglia start fading,” Bhaskar says. “They don’t do their job efficiently as we age”

Bhaskar’s lab has also developed and tested a vaccine based on virus-like particles (VLP) that clears tau from the neurons and appears to improve cognitive function – in mice.

“Blocking these tau tangles with various means, including our VLP-based Alzheimer’s vaccine, is sufficient to halt brain inflammation and feed-forward induction of tangle pathology – and in turn show improvement in recognition and spatial memory,” Bhaskar says.

Mice bred to develop tau tangles in their brains actually improved their performance in several tests after being administered the vaccine, he says.

The next phase of research is being conducted in macaques – primates whose brains more closely resemble humans. Research conducted so far in collaboration with the University of California, Davis, and the California National Primate Research Center shows the vaccines are safe, provide a robust immune response against tau and have no side effects, Bhaskar says.