New Mexico Approves Master of Science in Anesthesia Program at UNM

Life in the Balance

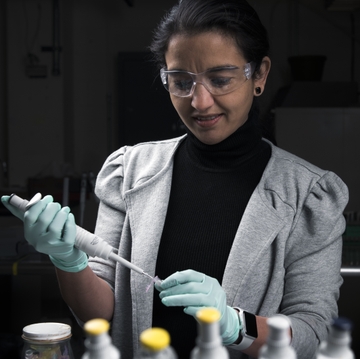

UNM Alumna Harshini Mukundan Creates a Stellar Research Career on Her Own Terms

Harshini Mukundan, PhD, juggles a dizzying number of responsibilities - while somehow making it all look effortless.

As an administrator in the Chemistry Division at Los Alamos National Laboratory, she serves as Deputy Group Leader for Physical Chemistry and Applied Spectroscopy and Team Leader in Chemistry for Biomedical Applications. The 2003 graduate from UNM's Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program is also a teacher, as well as a devoted parent and spouse, who, in her spare time, participates in traditional Indian dance.

But in her role as a research scientist, Mukundan is laser-focused on finding solutions to some of the most urgent health concerns facing humanity. At LANL she has developed diagnostic assays for tuberculosis and helped create technology to detect breast cancer and influenza. Her current - highly ambitious - research agenda centers on finding a universal method for identifying infectious disease.

Munkundan's lab has unraveled some of the common methods by which disease-causing organisms interact with a human host in hopes of creating a mechanism to mimic what the body already does naturally.

"All pathogens support or secrete biomarkers that are recognized by our innate immune system," she says, adding that many of these molecules are highly conserved. "The body recognizes conserved signatures. It looks at the commonality and uses that to mount a response."

These molecules are not easily detected in the bloodstream, but they are carried throughout the body by hitchhiking on HDL and LDL cholesterol proteins ("My buzzword for them is the 'biological taxi service,'" she says).

Mukundan and her collaborators are working on sensor technology that can liberate these biomarkers from their cholesterol hosts and measure them, providing a rapid readout of what type of infection they're signaling.

While the lab's work has national defense applications, it also has obvious relevance in clinical health care and is already being assessed for its use in diagnosing disease in the field. It has been tested in South Korea, Uganda and Kenya, Mukundan says, and could provide a quick way to distinguish a bacterial from a viral infection.

Mukundan's path to a leadership role at the nation's premier national laboratory started in a small town in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, where her father was in banking and her mother was a teacher.

She earned her undergraduate degree in microbiology from the University of Delhi in 1995. "It seemed cool," she says. "I liked biology and I always wanted to do medicine or biology." She went on to complete a master's in microbiology at Barkatullah University in Bhopal, with her thesis research conducted at India's National Institute of Immunology.

Her lab work there centered on drug-resistant cancer cell lines. "There were pretty awesome researchers working at NII," Mukundan says. "I got to meet a lot of really cool people. Essentially, it was just the exposure, and then I decided I wanted to do a PhD."

She and her husband, LANL staff scientist Rangachary Mukundan, came to the U.S. for their doctoral work. He earned his PhD in materials science at the University of Pennsylvania and joined LANL as a postdoctoral fellow in 1997.

Harshini initially was accepted at Penn for her PhD, but transferred to The University of New Mexico when her husband got his job at Los Alamos. As a late arrival in UNM's Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, she started by rotating through several labs, where she met Nancy Kanagy, PhD, now chair of the Department of Cell Biology & Physiology.

"I really liked Nancy," Mukundan says. "I liked her work ethic and approach to balance. She has this way of making you feel very welcome."

At the time, Kanagy was working on alpha adrenergic receptors and their role in cardiovascular disease, which Mukundan found interesting. Mukundan started by exploring a hypothesis involving the movement of calcium ions in cells that soon turned out to be incorrect.

"I definitely proved that the hypothesis was wrong," she says. "We got a paper out of it, but that research was at a dead end. We had to make a project change."

With Kanagy and fellow Cell Biology professor Thomas Resta, Mukundan devised a new project. "It was looking at gender differences in hypertension and the role of estrogen in erythropoietin regulation," she says.

In putting together the research proposal that would lead to her dissertation on how estrogen regulates of erythropoietin gene expression during hypoxia. "Nan and Tom were heavily involved and helped a lot, obviously, and we got it," she says, adding that the setback taught her a valuable lesson.

"It looks like a big bummer when your original project doesn't work, but in retrospect, I learned how to write," she says. "It made me altogether much more confident. Sometimes you have what appears to be a big tragedy but it actually works out for the better."

Mukundan says she experienced some reactions when she first came to the U.S. that were "a little bit racist," she sometimes felt she was treated differently because she was a woman. But at UNM she felt supported.

"In Nan and Tom's team I found acceptance," Mukundan says. Kanagy, who was starting a family, became a friend and mentor. "I think it kind of subconsciously does teach you that women can be great scientists, good mothers - and perpetually tired."

Mukundan and her husband lived in Santa Fe while she was doing her lab research, requiring a daily commute to the UNM campus in Albuquerque. "She stayed at my house," Kanagy recalls. "Sometimes it was really late to drive back to Santa Fe."

Mukundan showed an aptitude for research, Kanagy says. "Harshini was unafraid of challenges," she recalls. "Early on, she was not daunted by having a hard problem to solve and taking this on. She used very creative approaches."

Mukundan was unflappable in the face of the failure of her first research project, Kanagy says. "'Courageous' might be the right word - or at least unintimidated by difficulty," she says. "When we she had to switch gears she was very resilient. She developed a whole bunch of new methods to answer this question."

Kanagy also appreciates her friend's ability to keep the many commitments in her life in balance.

"She's very human and cared very deeply about her family and cared about my family," she says. "Even then, she was doing traditional Indian dance while commuting an hour each way. When I think of Harshini, she has a great smile and she just invites people in - she's just a pleasure to have around."

When Mukundan defended her dissertation in 2002, soon after having her first child, Kanagy urged her to pursue postdoctoral research at another university, but Mukundan instead took a job at QTL Biosystems, Santa Fe a biotech startup, where she worked for two years on biosensor technology.

In 2006 Mukundan won a postdoctoral position at LANL in the lab of Dr. Basil Swanson, where she wrote a National Institutes of Health grant for research on developing a diagnostic tool for tuberculosis. "We got that proposal and I still work on TB today," she says. "That's how we got started."

After graduating to become a full member of the LANL faculty, Mukundan has become a mentor in her own right. Earlier this year, she was recognized as one of 125 IF/THEN Ambassadors by the American Association for the Advancement of Science for her support of young women in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) at LANL.

IF/THEN is a national initiative of Lyda Hill Philanthropies that seeks to further women in STEM fields by recognizing innovators and inspiring the next generation of researchers.

Although scientific careers can be incredibly demanding, Mukundan says she learned from her UNM colleagues "you can have a good career and have a family and have work-life balance. That makes people want to go into science."